In the Mokṣopāya, the “Means to Liberation,” we have the least mythological and most detailed account of cosmogony, especially its very early stages, found in any Sanskrit book known to me. The Mokṣopāya, as described here earlier (April 13, 2012), is an unrevised and considerably more original version of what has become known as the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha. Through the kindness of a friend, I have now acquired the recently published large Sanskrit volume giving its utpatti-prakaraṇa, the section (prakaraṇa) on the origination (utpatti) of the world (Mokṣopāya, Das Dritte Buch: Utpattiprakaraṇa, Kritische Edition von Jürgen Hanneder, Peter Stephan und Stanislav Jager, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2011). The fact that ultimately the world has never really arisen, according to this text, does not prevent this text from teaching cosmogony, which it here does. A large percentage of the Mokṣopāya (and Yoga-vāsiṣṭha) is teaching stories used to illustrate its ideas. Only a small percentage directly states the teachings. The core account of cosmogony is found in chapter twelve of the utpatti-prakaraṇa or third section of the Mokṣopāya. No translation of this yet exists. Martin Gansten informs me that the projected translation of this section by him, announced in The Mokṣopāya, Yogavāsiṣṭha and Related Texts (2005, p. 4), had to be abandoned years ago. Roland Steiner informs me that it is years away in the German translation that is underway by him as part of the Mokṣopāya Project, funded by two German universities. I have not heard of any English translation that is either planned or begun. I have therefore translated this chapter myself, since it is of fundamental importance for Book of Dzyan research.

An altered version of this chapter is, of course, found in the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha. The only complete translation of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha is that by Vihāri-lāla Mitra, published in four large volumes, 1891-1899 (Calcutta). Unfortunately, it is more of an interpretation than a translation. About this translation B. L. Atreya writes in his extensive 1936 study, The Philosophy of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha (p. 31), that it “is praiseworthy only as an effort, not as a translation. It is not reliable, being wrong at numberless places. It is altogether useless for a student of the philosophy of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha.” While it may not be useless for other purposes, so that the years of labor bestowed by Mitra on the translation were not in vain, I would agree that it is useless for those who want to study the philosophy. It is just too loose. Moreover, Mitra often adds things of his own that are not in the Sanskrit. At the same time, he often omits the more difficult terms, simply leaving them out of his translation. Thus, from his translation, a reader cannot know what is and is not in the Sanskrit text. Since his time, a few summarized and paraphrased translations of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha have been published (e.g., Vasiṣṭha’s Yoga, by Swami Venkatesananda). But for the chapter in question they are too vague and general to be of much use for comparative studies of its cosmogony.

B. L. Atreya gives a general summary of this chapter in his book, The Philosophy of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, on pp. 188-189. He then notes: “The above passages are freely rendered into English, as literal translation would appear to be unintelligible.” Intelligible or not, a literally accurate translation (as accurate as English allows) is necessary for comparative research on cosmogony, especially the detailed cosmogony of the Book of Dzyan. Atreya probably here also alludes to the fact that while it is usually possible to get the text’s general meaning, its precise meaning is often uncertain. The Yoga-vāsiṣṭha uses some unusual words whose exact meaning has not been fully ascertained. This is even more the case in the Mokṣopāya, where considerably more unusual words are found. These have often been changed into familiar words in the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, sometimes changing the meaning entirely. On more common words, there are always questions about which of their several meanings are intended. These include many technical terms, whose meanings vary from one system to another. The metrical verse format means that in many cases more than one way to construe the words into sentences is possible. A verse can be taken in various ways. So while one may get the general sense well enough, the precise meaning cannot always be arrived at with certainty. Along with this is the fact that Sanskrit technical terms simply have no accurate English equivalents in many cases. The Yoga-vāsiṣṭha and Mokṣopāya use, for example, several different terms for consciousness, with varying shades of meaning. Sometimes these are used as synonyms, and sometimes they are not. Even when these shades of meaning are understood by the translator, they often cannot be rendered into English for lack of equivalents. These two facts make it difficult to produce a complete and literally accurate translation. Despite the difficulty, a literally accurate translation of chapter twelve of the third section of the Mokṣopāya must be attempted.

Sanskrit texts written in verse are normally read in India with the help of commentaries, because sentences are often somewhat abbreviated when put into verse. There exists a very helpful commentary on the Mokṣopāya, written by Bhāskara-kaṇṭha, but unfortunately we do not have it complete. It so happens that the extant fragment of this commentary on the utpatti-prakaraṇa breaks off after three and a half verses of chapter twelve (Bhāskarakaṇṭhas Mokṣopāya-ṭīkā: Die Fragmente des 3. (Utpatti-)Prakaraṇa, ed. Walter Slaje, Graz, 1995, pp. 186-187). For the construal and meaning of the remaining verses of this chapter we have little help. The commentary by Ānanda-bodhendra Sarasvatī on the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha comments on a text that differs substantially from the Mokṣopāya, and does so from the standpoint of Advaita Vedānta (which is not the standpoint of the Mokṣopāya). Nonetheless, I have consulted this commentary and taken help from it where possible. These cases have been clearly noted.

For most of this chapter of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha there is also a carefully done translation by Samvid that attempts to be literally accurate. It is found in The Vision and the Way of Vasiṣṭha (Madras: Indian Heritage Trust, 1993, pp. 141-147). This book is the Vāsiṣṭhadarśanam, 2,461 of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha’s approximately 28,000 verses, selected by B. L. Atreya as giving the philosophy of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha. To Atreya’s collection, first published in Sanskrit in 1936, is here added a careful English translation by Samvid. He writes (p. xlviii): “The translator is aware that his obsession with exactitude in translation has led to complex constructions in several places and perhaps, some transgression of the normally accepted usage of the language. The translator hopes that the readers will pardon this apparent shortcoming, since the advantages of the translator’s approach outweigh those of the usual paraphrases which are presented as translations.” Where the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha and the Mokṣopāya coincide, I have found this translation to be very helpful, and have adopted some phrases from it. The extensive differences between Samvid’s translation and my translation mostly reflect the considerable differences between the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha and the Mokṣopāya, and sometimes the different possibilities for English translation of the same Sanskrit.

For the meaning of the unusual words found in the Mokṣopāya (and often in the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha), and to determine as accurately as possible the meaning intended for the more common words, I have spent many hours searching for and checking other passages in which they occur in the Mokṣopāya, and for glosses of them in the extant portions of Bhāskara-kaṇṭha’s commentary on the Mokṣopāya (sections one through four, edited by Walter Slaje, 1993-2002). This has been made easily possible through the courtesy of Walter Slaje, in supplying a searchable electronic file of these four volumes to the GRETIL (Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages) project, available at: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/1_sanskr/6_sastra/3_phil/vedanta/motik_au.htm. This searchable electronic file has allowed me to check a substantial portion of the Mokṣopāya for these terms, to a degree that was not possible with the physical printed volumes. It is never safe to attempt to translate a piece of a large work before the whole has been studied. Since it has not been possible for me to study the whole Mokṣopāya, due to its great size and also because much of it still remains unpublished, I have derived much benefit from Jürgen Hanneder’s 2006 book, Studies on the Mokṣopāya (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag). Hanneder’s book has provided a very helpful perspective on the whole text.

The Sanskrit text of this chapter has been very carefully edited, as far as I can judge. It has been a joy to work with. We have Jürgen Hanneder to thank for the extremely accurate edition of this chapter. This excellent scholarship provides a solid basis for reliable research. The translation of this chapter has likewise been done as carefully as possible, and it should provide reasonably accurate access to this important material on cosmogony. Sanskrit technical terms are given in parentheses after their English translations, which can only be approximate. Additions to what is actually stated in the Sanskrit text are given in square brackets. Sometimes they fill in what a pronoun refers to, based on its gender in Sanskrit. When explanatory material is added in brackets to make sense of a line, references to its source in other passages of the text are given in the “Translation Notes” following the translation. These are marked with asterisks. The “Translation Notes” also include some of the sources from which I derived the meaning of unusual terms not found in our Sanskrit dictionaries (or not found there in the appropriate meaning), and explain my choice of translation terms used for them.

The first several verses give an unusually detailed account of the initial stages of the arising of the world. In this text, unlike the Book of Dzyan, the ultimate (here called brahman) is equated with pure consciousness (cin-mātra). “Creation,” or more accurately and literally “emanation,” is called its radiance (kacana), which becomes a functioning consciousness (as opposed to pure consciousness). As this functioning consciousness takes on a sense of self-consciousness the world condenses into manifestation. The idea of self-consciousness (ahaṃkāra) is also found in Sāṃkhya, where it is often applied to the human constitution, so has sometimes been translated as ego or egoism or egotism. In verses 13 onward we see another idea that is found in Sāṃkhya, what is usually translated as the subtle elements (tanmātra). Both here and in Sāṃkhya, the principle of self-consciousness (ahaṃkāra) produces the subtle elements. The subtle elements in turn produce the great elements (mahā-bhūtas): space (or ether), air, earth, fire, and water. These latter elements are apparently used symbolically, and not as the physical elements of those names. In order to follow this chapter of the Mokṣopāya, it is necessary to know the Sāṃkhya teaching on the subtle elements and great elements. According to Gauḍapāda’s commentary on Sāṃkhya-kārikā, verse 3:

(1) the subtle element sound (śabda) generates the great element space or ether (ākāśa).

(2) the subtle element touch (sparśa) generates the great element air (vāyu).

(3) the subtle element smell (gandha) generates the great element earth (pṛthivī).

(4) the subtle element form (rūpa) generates the great element fire (tejas).

(5) the subtle element taste (rasa) generates the great element water (apas).

It seems that the Mokṣopāya is willing to refer to the subtle elements either by their own names, sound (śabda), etc., or by the names of the great elements that they produce, space (ākāśa), etc. Thus, the Mokṣopāya may refer to the subtle element of space, meaning the subtle element of sound. This must be noted to avoid confusion.

Mokṣopāya, Section 3, Chapter 12

etasmāt paramāc chāntāt padāt parama-pāvanāt |

yathedam utthitaṃ viśvaṃ tac chṛṇūttamayā dhiyā || 1 ||

1. Listen with utmost understanding to how this universe has arisen from that highest quiescent place, of the highest purity.

suṣuptaṃ svapnavad bhāti bhāti brahmaiva sargavat |

sarvam ekaṃ ca tac chāntaṃ tatra tāvat kramaṃ śṛṇu || 2 ||

2. [Just as] one who is asleep appears as dream, [so] also brahman appears as creation (“emanation”). That quiescent [brahman] is the all and the one. In regard to this [emanation of the universe], listen to the sequence in its entirety.

tasyānanta-prakāśātma-rūpasyātata-cin-maneḥ |

sattā-mātrātma kacanaṃ yad ajasraṃ svabhāvataḥ || 3 ||

tad ātmani svayaṃ kiñcic cetyatām iva gacchati |

agṛhītārthakaṃ saṃvidīhāmarśana-sūcakam || 4 ||

3-4. The radiance (that is manifestation), having the nature of the mere state of existing (sattā) of that [brahman] whose form consists of the infinite light of the jewel of all-pervading consciousness (cit), ever by its inherent nature (svabhāva), in itself, by itself, becomes to a certain extent as if cognizable. Here, no objects are apprehended in consciousness (saṃvid), and there is no indication of conscious deliberation (marśana).

bhāvi-nāmārtha-kalanaiḥ kiñcid ūhita-rūpakam |

ākāśād aṇu śuddhaṃ ca sarvasmin bhāvi-bodhanam || 5 ||

5. Through the conceiving (kalana) of future names and objects [of the universe about to be manifested], its form becomes perceived to a certain extent, being subtler and purer than space (ākāśa). This is the awakening that is about to take place in all.

tatas sā paramā sattā satītaś cetanonmukhī |

cin-nāma-yogyā bhavati kiñcil labhyatayā tayā || 6 ||

6. Then that highest state of existing (sattā), now being ready for [functioning] consciousness (cetana) [as opposed to pure consciousness, cin-mātra],* becomes fit to be called consciousness (cit) due to this attainability [in speech or thought] to a certain extent.

ghana-saṃvedanāt paścād bhāvi-jīvādi-nāmikā |

sā bhavaty ātma-kalanā yadā yāntī parāt padāt || 7 ||

7. After that, from dense [i.e., undivided] cognition (saṃvedana), [comes that consciousness (cit) which is] called future individual souls (jīva), etc. It becomes the conception (kalanā) of self (ātman) when going from the highest place.

svataika-bhāvanā-mātra-sārā saṃsaraṇonmukhī |

tadā vastu-svabhāvena tanvas tiṣṭhanti tām imāḥ || 8 ||

8. [That consciousness (cit) whose] essence is only the single ideation (bhāvanā) of its own nature (svatā) is ready for cycling in the round of rebirth. Then, through the inherent nature (svabhāva) of the substance (vastu) [i.e., brahman = consciousness (cit)], these selves (tanū) establish it [in manifestation].

samanantaram etasyāḥ kha-sattodeti śūnyatā |

śabdādi-guṇa-bījaṃ sā bhaviṣyad-abhidhārtha-dā || 9 ||

9. Immediately thereafter, from that* arises the state of existing (sattā) of space, [which state of existing of space is] emptiness (śūnyatā). It, the giver of future names and objects, is the seed of the qualities (guṇa) beginning with sound.

*jīva-sattā, “the state of existing of the individual souls,” according to the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha commentator Ānanda-bodhendra, which also makes sense here in the Mokṣopāya.

ahantodeti tad-anu saha vai kāla-sattayā |

bhaviṣyad-abhidhārthe te bījaṃ mukhyaṃ jagat-sthiteḥ || 10 ||

10. After that the sense of individuality (ahaṃtā, lit. “I-ness”) arises, along with the state of existing (sattā) of time. In regard to future names and objects, these are the primary seed of the subsistence (sthiti) of the world.

tasyāś śakteḥ parāyās tu sva-saṃvedana-mātrakam |

etaj jālam asad-rūpam sad ivodeti visphurat || 11 ||

11. From this highest power (śakti) comes mere self-cognition (sva-saṃvedana). Manifesting, this web in the form of the unreal (asat) arises as if real (sat).

evam-prāyātmikā sā cid bījaṃ saṅkalpa-śākhinaḥ |

tatrāpy ahaṅkāra-karas sa tat-spandatayā marut || 12 ||

12. That consciousness (cit), of such kind, is the seed of the tree of creative thought (saṃkalpa). There also is the maker of self-consciousness (ahaṃkāra). That [self-consciousness], as the motion (spanda) of that [consciousness], is wind.

cid ahantāvatī vyoma-śabda-tanmātra-bhāvanāt |

svato ghanībhūya śanaiḥ kha-tanmātraṃ bhavaty alam || 13 ||

13. Consciousness (cit) possessing the sense of individuality (ahaṃtā), gradually becoming dense, as a result of the ideation (bhāvanā)* of the subtle element (tanmātra) of sound or space from itself, fully becomes the subtle element of space.

*i.e., the developing in thought.

bhāvi-nāmārtha-rūpaṃ tad bījaṃ śabdaugha-śākhinaḥ |

pada-vākya-pramāṇāḍhya-veda-vṛnda-vikāri tat || 14 ||

14. That, in the form of future names and objects, is the seed of the tree of the multitude of sounds. It has for its products the multitude of knowledge (veda), rich in the measures (pramāṇa) of words and sentences.

tasmād udeṣyaty akhilā jagac-chrīś śabda-rūpiṇaḥ

śabdaugha-nirmitārthaugha-pariṇāma-visāriṇī || 15 ||

15. From that [seed] in the form of sound will arise the entire splendor of the world, diffusing as the transformations of the multitude of objects formed by the multitude of sounds.

cid evam-parivārā sā jīva-śabdena kathyate |

bhāvi-śabdārtha-jālena bījaṃ bhūtaugha-śākhinaḥ || 16 ||

16. This consciousness (cit) having such a retinue is described by the word “individual soul” (jīva). By means of the web of future sounds and objects it is the seed of the tree of the multitude of beings.

caturdaśa-vidhaṃ bhūta-jātam āvalitāmbaram |

jagaj-jaṭhara-yantraughaṃ prasariṣyati vai tataḥ || 17 ||

17. From that will flow forth the fourteenfold class of beings [of the fourteen worlds],* whose space is enclosed [in the egg of Brahmā],* the multitude of instruments (yantra) in the womb of the world.

asamprāptābhidhā-sārā cij jīvatvāt sphurad-vapuḥ |

yā saiva sparśa-tanmātraṃ bhāvanād bhavati kṣaṇāt || 18 ||

18. The same consciousness (cit) that in its essence has not acquired names, [but that] in its form is manifesting because of being the individual soul (jīva), becomes the subtle element of touch in a moment through ideation (bhāvanā).

pavana-skandha-vistāraṃ bījaṃ sparśaika-śākhinaḥ |

sarva-bhūta-kriyā-spandas tasmāt samprasariṣyati || 19 ||

19. [The subtle element of touch is] the seed of the single tree of touch, [a seed] whose expansion is the branches that comprise [the element] air. From that will flow forth the motion (or vibrations, spanda) in the form of all beings and activities.

tatra yaś cid-vilāsena prakāśo ’nubhavād bhavet |

tejas-tanmātrakaṃ tat tad bhaviṣyad-abhidhārtha-dam || 20 ||

20. There, the light that will come into existence by the play of consciousness (cit) due to [its self-]experience* is the subtle element of fire. It is the giver of future names and objects.

tat sūryādi-vijṛmbhābhir bījam āloka-śākhinaḥ |

tasmād rūpa-vibhedena saṃsāraḥ prasariṣyati || 21 ||

21. That, through its manifestations as the sun, etc., is the seed of the tree of light. From that, through the division of forms (rūpa), the cycle of rebirth will flow forth.

bhavac caturṇām avatas tatas sata ivāsataḥ |

svadanaṃ tasya saṅghasya rasa-tanmātram ucyate || 22 ||

22. Being below the four [other subtle elements, arising] from that [principle of self-consciousness, which although actually] non-existing is as if existing,* is tasting. Of this group [of subtle elements], it is called the subtle element of taste.

bhāvi-vāri-vilāsātma tad bījaṃ rasa-śākhinaḥ |

anyo’nyāsvadanenāsmāt saṃsāraḥ prasariṣyati || 23 ||

23. That [subtle element of taste], having the nature of the manifestation (“play,” vilāsa) of future water, is the seed of the tree of taste. From that, by mutual tasting, the cycle of rebirth will flow forth.

bhaviṣyad-gandha-saṅkalpa-nāmāsau kalanātmakā |

saṅkalpātmā sa-saugandha-tanmātratvaṃ prayacchati || 24 ||

24. That called the creative thought (saṃkalpa) of future smell, consisting of conception (kalanā), having the nature of creative thought (saṃkalpa), gives forth the subtle element of smell.

bhāvi-bhū-golakatvena bījam ākṛti-śākhinaḥ |

sarvādhārātmanas tasmāt saṃsāraḥ prasariṣyati || 25 ||

25. As the future sphere of the earth it is the seed of the tree of shapes (ākṛti, i.e., the modes of appearance of all things). From that, having the nature of the support of all, the cycle of rebirth will flow forth.

citā vibhāvyamānāni tanmātrāṇi parasparam |

svayaṃ pariṇatāny antar ambunīva nirantaram || 26 ||

26. Being ideated by consciousness (cit), the subtle elements are continually transformed one by the other of their own accord within [consciousness] like [water] in water.*

tathaitāni vimiśrāṇi viviktāni punar yathā |

na śuddhāny upalabhyante sarva-nāśāntam eva hi || 27 ||

27. These [subtle elements], so being mixed, are not perceived as again distinct and pure up to the very end at the universal destruction.

saṃvitti-mātra-rūpāṇi sthitāni gaganodare |

bhavanti vaṭa-jālāni yathā bīja-kaṇāntare || 28 ||

28. Situated in the womb of space in the form of mere consciousness (saṃvitti), they are like hosts of banyan trees inside tiny seeds.

prasavaṃ paripaśyanti śata-śākhaṃ sphuranti ca |

paramāṇv-antare mānti kṣaṇāt kalpībhavanti ca || 29 ||

29. They picture progeny and manifest a hundred branches. They are contained inside an ultimate atom (paramāṇu) and in a moment become all-creating thought (kalpa).

vivartam eva dhāvanti nirvivartāni santi ca |

cid-veditāni sarvāṇi kṣaṇāt piṇḍībhavanti hi || 30 ||

30. Being without modification (vivarta) they flow [out to become] the [apparent] modification [that is the world], and experienced (or felt, vedita) in consciousness (cit) they all become solidified in a moment.

tanmātra-gaṇam etat sā sva-saṅkalpātmakaṃ citiḥ |

vedanāvasare ’ṇv-augham anākāraiva paśyati || 31 ||

31. This group of subtle elements is that consciousness (citi) consisting of its own creative thought (saṃkalpa). In the scope of experience (vedana) [that consciousness] which is quite without forms (ākāra, modes of appearance) pictures [into existence] the multitude of atoms (aṇu).

bījaṃ jagatsu nanu pañcaka-mātram asya

bījaṃ parā vyavahitā citi-śaktir ādyā |

tajjaṃ tad eva bhavatīti sadānubhūtaṃ

cin-mātram ekam ajam ādyam ato jagacchrīḥ || 32 ||

32. Surely the seed of the worlds is only the group of five [subtle elements]. The seed of that is the concealed highest primordial power of consciousness (citi-śakti). That [group of five subtle elements] indeed becomes born from that [power of consciousness]. Thus is always experienced (or known, anubhūta) the one unborn primordial pure consciousness (cin-mātra). From it [arises] the splendor of the world.

Comparison with the Book of Dzyan

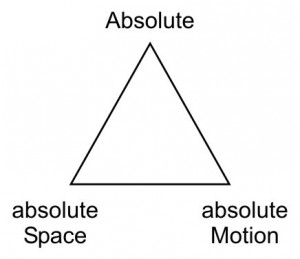

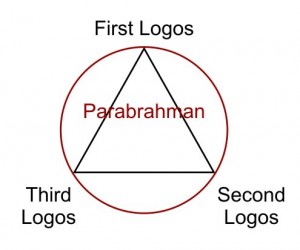

The Mokṣopāya provides an account of cosmogony that is complementary to the cosmogony account given in the Book of Dzyan. The Mokṣopāya account is given from the standpoint of an ultimate consciousness, while the Book of Dzyan account is given from the standpoint of an ultimate substance. According to The Secret Doctrine (vol. 1, pp. 14-15), these are the two aspects under which our finite intelligence must symbolize or conceive the one ultimate “be-ness.” A very helpful comparison of the two systems of cosmogony was made by the Advaita Vedāntin Theosophist T. Subba Row, in his article, “A Personal and an Impersonal God.” The Yoga-vāsiṣṭha has long been considered an Advaita Vedānta work, and from the terminology used by T. Subba Row, it is clear that this was his source for describing the Advaita system. He uses the term cid-ākāśa, which is not found in the standard Advaita Vedānta works of Śaṅkarācārya, etc., and also cin-mātra and cit-śakti, all of which are basic terms of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha. Indeed, in T. Subba Row’s third lecture on the Bhagavad-gītā (December 29, 1886), he says about the gāyatrī that: “It is stated to be Cit-śakti by Vasiṣṭha” (T. Subba Row Collected Writings, comp. Henk J. Spierenburg, vol. 2, p. 511). In comparing the two systems of cosmogony, he refers to the system of the Book of Dzyan as the Arhat system. He concludes in this article:

“Now, it will be easily seen that the undifferentiated Cosmic matter, Purush, and the ONE LIFE of the Arhat philosophers, are the Mulaprakriti, Chidakasam and Chinmatra of the Adwaitee philosophers. As regards Cosmogony, the Arhat stand-point is objective, and the Adwaitee stand-point is subjective. The Arhat Cosmogony accounts for the evolution of the manifested solar system from undifferentiated Cosmic matter, and Adwaitee Cosmogony accounts for the evolution of Bahipragna from the original Chinmatra. As the different conditions of differentiated Cosmic matter are but the different aspects of the various conditions of pragna, the Adwaitee Cosmogony is but the complement of the Arhat Cosmogony. The eternal Principle is precisely the same in both the systems and they agree in denying the existence of an extra-Cosmic God.”

(The Theosophist, vol. 4, March 1883, pp. 138-139; reprint in Five Years of Theosophy, London, 1885, pp. 208-209; Second and Revised Edition, London, 1894, p. 133; reprint in A Collection of Esoteric Writings of T. Subba Row, published by Tookaram Tatya, Bombay, 1895, pp. 97-98; reprint in T. Subba Row Collected Writings, compiled by Henk J. Spierenburg, San Diego, 2001, vol. 1, p. 127; the concluding portion of the article, including this paragraph, was mistakenly left out in the reprint in Esoteric Writings of T. Subba Row, Second Edition—Revised and Enlarged, Madras, 1931, ending on p. 470; reprint, 1980)

A few points of comparison between the Mokṣopāya chapter (section 3, chapter 12) and the “Book of Dzyan” stanzas given in The Secret Doctrine may be noted:

Mokṣopāya verses 3 and 8 say that manifestation is due to the inherent nature (svabhāva) of brahman, or pure consciousness. Similarly, the Book of Dzyan teaches that manifestation is due to the inherent nature (svabhāva) of the one element.

Mokṣopāya verse 9 describes the state of existing of space as emptiness, śūnyatā. While the relatively few stanzas we have from the Book of Dzyan do not explicitly mention emptiness, their use of Mahāyāna Buddhist terminology would indicate that it is part of their system. It is basic to Mahāyāna Buddhism. Note that for “space” the Mokṣopāya here uses the generic “kha,” and that this is before the manifestation of the element “space” (or “ether”), ākāśa.

Mokṣopāya verse 12, describing the principle of self-consciousness (ahaṃkāra), says that as the motion (spanda) of consciousness (cit) it is wind (marut). Again, this is before the manifestation of the element wind or air. So perhaps this wind is the fohat of the Book of Dzyan, the whirlwind that hardens the atoms.

Mokṣopāya verse 11 in fact speaks of śakti (“power”), used by T. Subba Row as a synonym of fohat, and the concluding Mokṣopāya verse 32 makes it very clear that the power of consciousness, citi-śakti, is responsible for the manifestation of the worlds. This is very much like fohat as found in the Book of Dzyan.

Translation Notes:

verse 2: The “[Just as] . . . [so]” are added by me following the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha commentator Ānanda-bodhendra’s yathā . . . tathā. The word tāvat is glossed by the Mokṣopāya commentator Bhāskara-kaṇṭha as sākalya, “entirety,” which I have followed. The translation by Samvid in The Vision and the Way of Vasiṣṭha (p. 141, no. 406) takes the word tāvat as “first,” which is equally plausible.

verses 3-4: The word kacana, which I have translated as the “radiance (that is manifestation),” is not in the dictionaries, neither the Sanskrit-Sanskrit dictionaries Śabdakalpadrumaḥ (5 vols.) and Vācaspatyam (6 vols.), nor in the Sanskrit-English dictionaries by Monier Monier-Williams and by Vaman Shivaram Apte (publication of the Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Sanskrit on Historical Principles has not yet progressed to the letter “ka”). It is glossed in the Mokṣopāya-ṭīkā here as sphuraṇa. Sphuraṇa can mean vibration or pulsation, radiance or shining, emanation or manifestation, etc. In the Mokṣopāya-ṭīkā, sphuraṇa and its cognates usually gloss words meaning manifestation (e.g., bhāti, avabhāsate, udeti, bhānam, bhāsanam, pratibhānam, etc.). Nonetheless, the primary meaning of kacana seems to be radiance or shining. Two meanings of the root kac are given in the Pāṇinīya-dhātu-pāṭha: bandhana, “binding” (1.181), and dīpti, “shining” (1.182). Another meaning is given elsewhere: rava, “sounding.” The relevant one here is obviously dīpti, “shining.” This meaning of kacana can be seen in the following verses:

saṃvid-ākāśa-kacanam idaṃ bhāti jagattayā |

“This radiance of the space of consciousness appears as the world.” (Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, section 6.2, chapter 171, verse 1)

yathā maṇiḥ prakacati svabhāsā’vyatiriktayā |

ātmano ’nanyayā sṛṣṭyā cid-vyoma kacitaṃ tathā ||

“Just as a jewel shines by its own light not separate from it, so the space of consciousness has radiated as creation not other than itself.” (Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, section 6.2, chapter 171, verse 28)

yaś cin-maṇiḥ prakacati prati-deha-samudgake |

“That jewel of consciousness shines in each ‘casket’ of body.” (Laghu-Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, section 3, chapter 1, verse 79)

The word sattā is from the present participle sat, “being,” with the suffix tā, “-ness.” So it is literally “beingness,” or “state of being,” “state of existing.” It has usually been translated simply as “existence” or “being.” It is a technical term. To show this, and to distinguish it from other words for being or existence, I have translated it as “state of existing.”

The extant manuscript of Bhāskara-kaṇṭha’s Mokṣopāya-ṭīkā commentary is missing folios here after the first three and a half verses, so we do not have his commentary for the rest of the verses of this chapter.

verse 5: The word kalana, which I have translated as “the conceiving,” is used in the Mokṣopāya in a meaning that is not given in the dictionaries. Its basic meaning, when found at the end of a compound (as it is here), is given in Vaman Shivaram Apte’s Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary as “causing, effecting.” It is here glossed by the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha commentator Ānanda-bodhendra as anusaṃdhāna, which in a related meaning is “planning, arranging, getting ready” (Apte, meaning no. 3). But in Advaita Vedānta, which this commentator follows, anusaṃdhāna usually means “inquiring into, examination, investigation, contemplation” (e.g., as the function of the citta in Sureśvara’s Pañcīkaraṇa-vārttika, verse 34; cp. Śaṅkarācārya’s Upadeśa-pañcaka, verse 1: bhava-sukhe doṣo ’nusaṃdhīyatām, translated by Y. Subrahmanya Sarma as “ponder deeply about the evil consequences of worldly pleasures”). He probably intends it as “contemplating.” At Yoga-vāsiṣṭha 3.13.2-4, where kalana is used five times, Ānanda-bodhendra glosses it as kalpana. Kalpana, like these and many other Sanskrit words, has multiple meanings, including “construction, fabrication, the forming, fashioning, making,” etc., often in the sense of “thought construction, forming an image in the mind, imagination,” etc. This appears to correctly reflect the meaning of kalana as found in the Mokṣopāya, as we may deduce by looking at its usage of the closely related term kalanā. Kalanā is described in Mokṣopāya 4.12.5 as saṅkalpa-rūpa, “in the form of saṃkalpa,” and is glossed in extant portions of Bhāskara-kaṇṭha’s commentary as saṃkalpa at least twice (1.15.7, 4.10.47). Saṃkalpa, too, has multiple meanings, including “thought, conceptual thought, conception, imagination, will, resolve,” etc. Here kalanā and saṃkalpa apparently refer to the formative thought or creative thought that forms or creates everything in the universe. I have used “creative thought” for saṃkalpa, and “conception” for kalanā. The feminine noun kalanā would refer to a particular conception, while the neuter noun kalana, which we have here, would be the act of conceiving. Hence, I have translated kalana as “the conceiving.” It would also have the sense of “the forming in thought.”

verse 6: We have in English few ways to distinguish cit, cetas, cetana, saṃvid, saṃvedana, etc., all meaning consciousness in some way.

*[functioning] consciousness (cetana) [as opposed to pure consciousness, cin-mātra]: Cetana as being lower is clearly distinguished from the ultimate cit (cin-mātra) at Mokṣopāya 3.7.2-14.

verse 8: The first word of this verse, svatā (joined with eka making svataika-), is apparently used in a meaning that is not recorded in the dictionaries. It is sva, “self, own,” plus the suffix tā, “-ness,” the state or condition of being something, in this case, itself. Svatā is found in a similar compound at Mokṣopāya (and Yoga-vāsiṣṭha) 3.3.14, svatodayaḥ, where Bhāskara-kaṇṭha glosses svatā as svabhāva, “inherent nature” (svatayā svabhāvena). Bhāskara-kaṇṭha again uses svatā (in the instrumental case, svatayā) at Mokṣopāya 4.31.32 to explain cin-mātra-svarūpe, the “essential nature of pure consciousness.” Svarūpa (“essential nature”) is practically synonymous with svabhāva (“inherent nature”). I have followed Bhāskara-kaṇṭha in understanding svatā in this way, and have translated svatā as “its own nature.”

While vastu can mean a “thing” in general, there is good reason to think that it is here used in its more specific meaning of “substance.” This is especially so when we find it in the compound, vastu-svabhāvena, “through the inherent nature of the substance,” as we have here. On this, see the section titled “Consciousness as a ‘Substance’,” in Jürgen Hanneder’s 2006 book, Studies on the Mokṣopāya, pp. 188-192. B. L. Atreya, too, in The Philosophy of the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, p. 572, understands that “the Absolute Reality . . . is a distinctionless, homogeneous Substance.” Likewise, Vihāri-lāla Mitra here translated vastu as the “divine essence,” adding in parentheses, “as the fallacy of the snake, depends on the substance of the rope” (vol. 1, p. 278). This, of course, is the famous example of where the illusion of the world arises on the basis of the real brahman, like the illusion of a snake arises on the basis of a real rope, an actual substance.

I understand tanvas (feminine nominative plural of tanū, “body, self”) to refer the “individual souls” (jīva) or “self” (ātman) spoken of in the previous verse. So I have taken it in the sense of its usage as a pronoun, “selves,” rather than as the noun, “bodies.”

verse 12: The word ahaṃkāra, literally “I-maker,” is well known as a major principle in the Sāṃkhya worldview. It has often been translated as “ego” or “egoism” or “egotism.” However, as it there applies to both a person and the cosmos, I have chosen to translate it as “[the principle of] self-consciousness” in my unfinished translation of the Sāṃkhya-kārikā. Here in this chapter of the Mokṣopāya, where it is clearly a cosmic principle, it is all more appropriate to translate it as “self-consciousness.”

The word spanda means “pulsation, vibration, motion, movement.” In this text, it is often associated with wind. See, for example, Yoga-vāsiṣṭha, section 6.2, chapter 84, verse 3, translated by Samvid, The Vision and the Way of Vasiṣṭha, p. 299, no. 1130:

yathaikaṃ pavana-spandam ekam auṣṇyānalau yathā |

cin-mātraṃ spanda-śaktiś ca tathaivaikātma sarvadā ||

“As wind and its motion are the same and as fire and its heat are identical, even so, mere Consciousness and its power of movement are always identical in essence.”

While we may speak of the pulsation or vibration of consciousness, we must speak of the motion or movement of wind. Since wind is mentioned here in verse 12, I have translated spanda as “motion.”

verse 17: *[of the fourteen worlds]: The Yoga-vāsiṣṭha commentator Ānanda-bodhendra says: caturdaśa-bhuvana-bhedāc caturdaśa-vidhaṃ prāṇi-jālaṃ, “the fourteenfold group of living beings due to the division of the fourteen worlds,” which makes perfect sense here.

*[in the egg of Brahmā]: This is suggested by the following jagaj-jaṭhara, “the womb of the world.”

The word āvalita is not found in Monier-Williams’ Sanskrit-English Dictionary, and is found in Vaman Shivaram Apte’s Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary only as “slightly turned” (from the Kādambarī), which is not relevant here. In the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha it is in the compound āvalitāntaram rather than āvalitāmbaram, as we have here in the Mokṣopāya. So Ānanda-bodhendra’s gloss, khena vyāptāntarālam, “that whose interior is pervaded by space,” does not really help us. Samvid translates āvalitāntaram in the Yoga-vāsiṣṭha verse as “moving all around the interior” (p. 144, no. 419), which also does not help us. We must now search for other occurrences of āvalita in the Mokṣopāya, where the meaning may be clearer, and in Bhāskara-kaṇṭha’s commentary thereon.

Two occurrences where the word is clearly āvalita (and not just valita preceded by a word ending in ā) can be found in the published volumes of the Mokṣopāya with the extant portions of Bhāskara-kaṇṭha’s Mokṣopāya-ṭīkā thereon, sections one through four, edited by Walter Slaje (1993-2002). These can now be easily searched, thanks to the electronic file of them that Dr. Slaje made available online through GRETIL (Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages). The first of these is in Mokṣopāya 1.19.46 (= Yoga-vāsiṣṭha 1.20.43), where we find āvalitaṃ gunaiḥ. Here the meaning is not entirely clear. In form, āvalita is a past passive participle, usually translated by English words ending in “-ed.” This occurrence tells us only that youth is “āvalita by/with good qualities.” It could be endowed (with), accompanied (by), surrounded (by), etc.

In the second occurrence, the meaning is clear. In Mokṣopāya 4.11.63 (= Yoga-vāsiṣṭha 4.11.64) āvalita clearly means “enclosed,” like the third meaning of valita (without the prefix “ā”) listed by Apte, “surrounded, enclosed.” Here is the verse:

yadaiva cittaṃ kalitam akalena kilātmanā |

kośa-kīṭavad ātmāyam anenāvalitas tadā ||

“When the mind (citta) is formed in thought (kalitam) by the partless self (ātman), this self is then enclosed (āvalita) by it like a pupa in a cocoon.”

Bhāskara-kaṇṭha here glosses āvalita with āvṛta, “covered, concealed, enclosed, surrounded,” giving the expected meaning.

For the compound āvalitāmbaram, since it begins with a past passive participle, we expect a bahuvrīhi compound such as: “that by which space is enclosed.” That which encloses space is the egg of Brahmā. However, this compound here appears to be an adjective describing the fourteenfold class of beings. They do not enclose space; they are enclosed by space inside the egg of Brahmā. So this meaning is not appropriate. Since we now know that āvalita means the same as valita in its meaning of “surrounded, enclosed,” we may search for the compound valitāmbaram. At Mokṣopāya 4.26.28 (= Yoga-vāsiṣṭha 4.26.29) we find valanā-valitāmbaram. There, valitāmbaram is glossed by Bhāskara-kaṇṭha as tābhiḥ valitaṃ vṛttam ambaraṃ yasya tat, “that whose space is surrounded, i.e., encircled, by those.” It is a battle scene, between the gods and the demons. It is their individual space that is surrounded by moving armies. This shows us how the compound āvalitāmbaram is to be understood here in verse 17, “whose space is enclosed.” It is apparently enclosed in the egg of Brahmā.

The word yantra, “instrument” (also “machine”), here presumably refers, if not to the beings themselves, to their bodies, minds, and faculties. The blood, flesh, and bones that compose the body are referred to as instruments, yantra, at Mokṣopāya 1.32.32 (= Yoga-vāsiṣṭha 1.33.35). At Mokṣopāya (and Yoga-vāsiṣṭha) 2.19.26 the faculties of action are compared to instruments (yantravat). Verse 27 speaks of the instrument of the mind (mano-yantra).

verse 20: *[its self-]experience: For the self-experience of consciousness, see Mokṣopāya 3.10.17 and its commentary by Bhāskara-kaṇṭha (same verse number in Yoga-vāsiṣṭha). See also the reference to “the inner self-experience of consciousness” from Mokṣopāya 6.230.10 given by Jürgen Hanneder, Studies on the Mokṣopāya, p. 188.

verse 22: *that [principle of self-consciousness, which although actually] non-existing is as if existing: For this idea, see verse 11.

verse 24: The Sanskrit phrase, sa-saugandha-tanmātratvaṃ, “that which has the state of the subtle element of good smell,” is a rather cumbrous way of saying “the subtle element of smell.” But it fits the meter.

verses 29, 31: The translation of the verb paśyati as “picture” is because, when creating in thought, things are “pictured,” not “observed.”