The Popol Vuh (or Popol Wuj) is the sacred book of the Maya. It gives their creation story, the stories of their gods and heroes, and a history of Maya kings. It includes the creation of human beings. This took three attempts, the first two of which ended in failure. Max Müller, in his 1862 review article on the Popol Vuh, misunderstood the book as describing four creations of humanity. These four were then cited in H. P. Blavatsky’s 1888 book, The Secret Doctrine, associating them with the four root-races taught there from the “Book of Dzyan.” These associations, made on an erroneous basis, are therefore also erroneous.

The first attempt at the creation of a human being is described only briefly in the Popul Vuh. This human being was made of earth and mud. It did not hold together well. It could not turn its head to look around. It spoke, but without sense. It would quickly dissolve in water. It could not walk. It could not multiply. So the disappointed creator gods destroyed it. (Sources for the first attempt: Recinos 1950, p. 86; Edmonson 1971, p. 19; Tedlock 1985, pp. 79-80; Tedlock 1996, pp. 68-69; Christenson 2003, pp. 78-79; Christenson 2004, pp. 26-27.) Tedlock notes that “the only creature made of mud is also the only one made in the singular” (1985, p. 257; 1996, p. 231).

The second attempt at the creation of human beings, and their subsequent destruction, is described at length in the Popol Vuh. They were made of carved wood, and were referred to as “poy,” variously translated as figures (Recinos), dolls (Edmonson), manikins (Tedlock), effigies (Christenson). They looked like people and they talked like people. They existed and they multiplied. They became numerous, the first to people the earth. But they had nothing in their hearts and they had no minds. They did not remember with thanks the gods who had created them. So they were destroyed, first by a flood sent by the great god “Heart of Heaven” (Recinos, Edmonson), or “Heart of Sky” (Tedlock, Christenson), their father.

It is here that Max Müller went astray, thinking that this closed the second attempt at creation. The text here adds that the body of man was made of tzité and the body of woman was made of reed or its marrow, before continuing with a lengthy description of other ways in which the figure/doll/manikin/effigy people made of carved wood were destroyed. Müller referred to tzité as a tree, but not as wood. So he erroneously took this as the third attempt at the creation of people (p. 335). The text continues, and at the end of its detailed descriptions of other ways in which these people were destroyed, it makes clear that these are the figure/doll/manikin/effigy people made of wood.

The text, when describing the planning of the second attempt at creation by the gods, refers to the people about to be created as “the formed people, the shaped people, the doll people, the made up people” (Edmonson, p. 21), and says that they are to be made of wood (Edmonson, p. 23). Then after all the descriptions of all the ways in which they were destroyed, we read “And thus was the destruction of the formed people, the shaped people” (Edmonson, p. 30). At the very end of this account, a few lines later, we read: “And it is said that the remainder are the monkeys that are in the forests today. That must be the remainder because their bodies were only fixed of wood by Former and Shaper. So the fact that the monkeys look like people is a sign of one generation of formed people, of shaped people, only puppets [poy, previously translated by him as dolls], and just carved of wood.” (Edmonson, pp. 30-31). This leaves no doubt that the end of the second attempt at creation is here being described, not the end of an erroneously postulated third attempt.

(Sources for the second attempt: Recinos 1950, pp. 89-93; Edmonson 1971, pp. 24-31; Tedlock 1985, pp. 83-86; Tedlock 1996, pp. 70-73; Christenson 2003, pp. 83-90; Christenson 2004, pp. 32-37.)

The third attempt at the creation of human beings comes much later in the Popul Vuh. Four men were created from ground yellow corn and white corn. They had no mother or father. They were not even begotten by the creator gods, but merely by a miracle (Recinos), power (Edmonson), sacrifice (Tedlock), miraculous power (Christenson), by means of incantation (Recinos), magic (Edmonson), genius (Tedlock), spirit essence (Christenson). They could talk, and they could walk. At first their sight was unlimited. They could see hidden things, and they could see at any distance. Aware of the unlimited knowledge that their unlimited sight gave them, they gave thanks to the creator gods. But then the gods wondered if it was right that the sight and knowledge of these four men equaled the sight and knowledge of the gods. So the great god Heart of Heaven/Heart of Sky limited their sight to things that were close, and with this their unlimited knowledge was also lost. They were then given wives, and these four pairs became the ancestors of the Maya people.

(Sources for the third attempt: Recinos 1950, pp. 165-170; Edmonson 1971, pp. 145-154; Tedlock 1985, pp. 163-167; Tedlock 1996, pp. 145-149; Christenson 2003, pp. 192-202; Christenson 2004, pp. 152-162.)

Christenson notes at the beginning of this account of the third attempt at the creation of human beings, the first successful one (2003, p. 192, fn. 452): “The Aztecs of Precolumbian Central Mexico believed that the earth had passed through five separate creations, each with the intent of forming beings capable of human expression. Only the fifth and final attempt was successful. . . . The Popol Vuh is consistent with this tradition in describing five separate creation attempts—the mountains and rivers, the animals and birds, the mud person, the wooden effigies, and now humankind.”

There are also other ways to count or correlate these creation attempts. Ralph Girard, in the 1979 English translation of his 1948 Spanish book, Esotericism of the Popul Vuh, classifies them into four ages of the world (p. 20): “The classification in the Popol Vuh embraces four cultural horizons, three prehistoric and one historic. They correspond to the four Ages or Suns of Toltec mythology, . . .” These from the Popul Vuh are, using Christenson’s terms for ease of comparison: the First Age is that of the creation of the animals and birds; the Second Age is that of the mud person; the Third Age is that of the wooden effigies; the Fourth Age is that of humankind.

. . . . . . .

References to the Popol Vuh in The Secret Doctrine,

compared with Max Müller’s review article on the Popol Vuh

S.D. vol. 1, p. 345: “In the Mexican Popol-Vuh, man is created out of mud or clay (terre glaise), taken from under the water.”

Max Müller, p. 334: “Then follows the creation of man. His flesh was made of earth (terre glaise). . . . He was soon consumed again in the water.”

This reference, both in Max Müller’s review article and in The Secret Doctrine, is misleading. It was not the creation of man, but only the first attempt, a failure; and the man made of earth and mud was then destroyed by the creator gods. Moreover, as noted by Tedlock, this description is in the singular in the Popol Vuh. So it seems that only one person was created. In the successful creation of people, later, they were made of ground corn.

S.D. vol. 2, p. 160: “The primitive ancestor, in Brasseur de Bourbourg’s “Popul-Vuh,” who — in the Mexican legends — could act and live with equal ease under ground and water as upon the Earth, answers only to the Second and early Third Races in our texts.”

This apparently refers to the first attempt at the creation of a human being in the Popol Vuh. The Popol Vuh says only that he was made of earth and mud. Neither Müller nor the Popol Vuh say anything about him being able to “act and live with equal ease under ground and water as upon the Earth.” On the contrary, the Popol Vuh says that this person would quickly dissolve in water.

S.D. vol. 2, p. 55 footnote.: “Remember . . . the Popol-Vuh accounts of the first human race, which could walk, fly and see objects, however distant.”

S.D. vol. 2, p. 96: “Again, in the ancient Quiché Manuscript, the Popol Vuh — published by the late Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg — the first men are described as a race “whose sight was unlimited, and who knew all things at once” : thus showing the divine knowledge of Gods, not mortals.”

S.D. vol. 2, p. 221: “. . . and others who . . . were born with a sight, which embraced all living things, and was independent of both distance and material obstacle. In short, they were the Fourth Race of men mentioned in the Popol-Vuh, whose sight was unlimited, and who knew all things at once.”

Max Müller, writing about what he describes as the fourth attempt at the creation of man, p. 337: “They could reason and speak, their sight was unlimited, and they knew all things at once.”

The first of these three quotations from The Secret Doctrine erroneously adds that “the first human race” could fly. Neither Müller’s review article nor the Popol Vuh itself say this. The second quotation similarly refers to them as “the first men.” In the Popol Vuh the first successful creation of people, resulting from the third attempt, had unlimited sight and knowledge only at first before it was taken away. The third quotation from The Secret Doctrine refers to them not as “the first human race” but as “the Fourth Race of men mentioned in the Popol-Vuh.” This quotation is immediately followed by “In other words, they were the Lemuro-Atlanteans.” This shows that Blavatsky in fact regarded them as early fourth root-race men rather than first root-race men. In The Secret Doctrine, the Lemurians are held to be third root-race, and the Atlanteans are held to be fourth root-race. The erroneous idea that the Popol Vuh teaches a fourth race of men comes from a misunderstanding by Müller, then erroneously equated with the fourth root-race by Blavatsky.

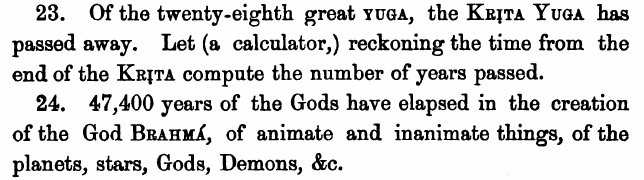

S.D. vol. 2, p. 97: “The Norse Ask, the Hesiodic Ash-tree, whence issued the men of the generation of bronze, the Third Root-Race, and the Tzite tree of the Popol-Vuh, out of which the Mexican third race of men was created, are all one.*

* See Max Müller’s review of the Popol-Vuh.”

Max Müller, p. 335: “Then follows a third creation, man being made of a tree called tzité, woman of the marrow of a reed called sibac.”

Müller misunderstood the Popol Vuh to teach a third creation in which man is made of a tzité tree, when in fact it was still describing the second attempt at creation, of people made of carved wood. Blavatsky then erroneously took this and equated it with the third root-race. Müller, in regarding this as a third creation, missed the fact that the Popol Vuh was describing people-like figures made of wood. So he referred to “a tree called tzité” rather than wood of the tzité tree. This led Blavatsky to erroneously equate the tzité tree with “the Norse Ask, the Hesiodic Ash-tree,” and to erroneously equate this tzité tree with the source “whence issued the men of the generation of bronze, the Third Root-Race.”

S.D. vol. 2, p. 181 footnote.: “In “Hesiod,” Zeus creates his third race of men out of ash-trees. In the “Popol Vuh” the Third Race of men is created out of the tree Tzita and the marrow of the reed called Sibac. . . .”

Max Müller, p. 335: “Then follows a third creation, man being made of a tree called tzité, woman of the marrow of a reed called sibac.”

Müller’s erroneous postulation of a third creation in which man is made of a tzité tree has already been noted, as has Blavatsky’s taking this and equating it with the third root-race, and Blavatsky’s equating the tzité tree with the ash-tree as the source of the third race of men. Now to Müller’s phrase, “woman of the marrow of a reed called sibac.” Brasseur de Bourbourg spells the word as zibak (pp. 26-27). Why it was changed to sibac in Müller’s review article is unknown. Brasseur de Bourbourg, who leaves it untranslated, has a footnote about it (p. 26): “Zibak, c’est la moelle d’un petit jonc dont les indigènes font leurs nattes, dit un vocabulaire manuscrit; un autre ajoute que c’est le sassafras.” Malpas translated this as: “Zibak: the pith of a little rush or reed of which the natives make their mats, says a MS. vocabulary. Others say it is sassafras” (The Theosophical Path, vol. 37.3, 1930, p. 211). There is a question of whether this word refers to the reed itself or to its pith. This has some significance for Blavatsky’s statement given in the rest of her footnote, quoted below, about this word referring to an egg. For as noted by Guthrie regarding “the pith of one kind of reeds” (The Word, vol. 2, 1905, p. 80): “Now it is evident that the root-signification is here the same as that of an egg, the inside being the most valuable part.”

The word zibak is taken as the reed itself by Recinos, Edmonson, and Christenson; and is taken as its pith by Tedlock, and by the manuscript vocabulary referred to by Brasseur de Bourbourg. The various translators have notes about this word. They are given below, preceded by the sentence to which they refer.

Recinos 1950, p. 90: “Of tzité, the flesh of man was made, but when woman was fashioned by the Creator and Maker, her flesh was made of rushes.”

footnote 1, p. 90: “The Quiché name zibaque is commonly used in Guatemala to designate this plant of the Typhaceae family, which is much used in making the mats called petates tules in that country. Basseta says it is the part of a reed with which mats are made.”

Edmonson 1971, p. 26:

“Of tz’ite was the body of the man

When he was carved

By Former

And Shaper.

Woman reed was the body of the woman

Who was carved

By Former

And Shaper.”

footnote 681, p. 26: “Zibak is the cattail or bulrush (Typha angustifolia) used for matting. Real men were later made of white and yellow corn; see line 4815 ff.”

Tedlock 1985, p. 84: “The man’s body was carved from the wood of the coral tree by the Maker, Modeler. And as for the woman, the Maker, Modeler needed the pith of reeds for the woman’s body.”

backnote, p. 260: “the pith of reeds: This is zibac; B. [Domingo de Basseta] gives ziba3 as “the pith or insides of a small reed.””

Tedlock 1996, p. 71: “The man’s body was carved from the wood of the coral tree by the Maker, Modeler. And as for the woman, the Maker, Modeler needed the hearts of bulrushes for the woman’s body.”

backnote, p. 235: “hearts of bulrushes: This is sib’aq [zibac], referring to the “heart” (FV, FX) or “pith or insides” (DB) of rushes of the kinds whose leaves are woven into mats (FV). This would be the white and fleshy (as opposed to green and fibrous) parts of rushes (including cattails), which can be found inside the lower parts of stalks.”

Christenson 2003, p. 85: “The body of man had been carved of tz’ite wood by the Framer and the Shaper. The body of woman consisted of reeds according to the desire of the Framer and the Shaper.”

footnote 125, p. 86: “This is the type of reed commonly used for weaving mats in Guatemala (Typha angustifolia).”

Christenson 2004, p. 33:

“Tz’ite his body the man

When he was carved

By Framer,

Shaper.

Woman,

Reeds therefore

Her body

Woman,

Desired to enter by Framer

Shaper.”

S.D. vol. 2, p. 181 footnote, continued: “In the “Popol Vuh” the Third Race of men is created out of the tree Tzita and the marrow of the reed called Sibac. But Sibac means “egg” in the mystery language of the Artufas (or Initiation caves). In a report sent in 1812 to the Cortes by Don Baptista Pino it is said : “All the Pueblos have their Artufas — so the natives call subterranean rooms with only a single door where they (secretly) assemble. . . . . These are impenetrable temples . . . . and the doors are always closed to the Spaniards. . . . . They adore the Sun and Moon . . . . fire and the great SNAKE (the creative power), whose eggs are called Sibac.””

This footnote goes with this sentence: “In the Secret Doctrine, the first Nagas — beings wiser than Serpents — are the “Sons of Will and Yoga,” born before the complete separation of the sexes, “matured in the man-bearing eggs† produced by the power (Kriyasakti) of the holy sages” of the early Third Race.” The Secret Doctrine refers to the third root-race as being “egg-born.” This is the significance of taking the word sibac to mean “egg.” Leaving aside the fact that the Popol Vuh is not here referring to a third creation of human beings, but only to the second, there is yet another difficulty. The phrase from the last sentence of the quotation from Don Baptista Pino, “whose eggs are called Sibac,” cannot be found in his report.

Blavatsky first quoted this material from Don Baptista Pino in Isis Unveiled, vol. 1, p. 557. The phrase in question is not found in the quotation as given there. Her source is there given as “Catholic World, N.Y., January, 1877: Article Nagualism, Voodooism, etc.” This article actually opens the April 1877 issue (vol. 25), and her quotation is from p. 7. The phrase in question is not found there. But, we may wonder, could it have been in a part that was not quoted in The Catholic World article?

Their quotation is referenced to “Noticias, pp. 15, 16.” This is a book written in Spanish, whose full title is: Noticias Historicas y Estadisticas de la Antigua Provincia del Nuevo-México, presentadas por su diputado en cortes D. Pedro Bautista Pino, en Cadiz el Año de 1812. Adicionadas por el Lic. D. Antonio Barreiro en 1839; y ultimamente anotadas por el Lic. Don José Agustin de Escudero, published in Mexico in 1849. A complete English translation of this book was made by H. Bailey Carroll and J. Villasana Haggard and published in Albuquerque in 1942 as: Three New Mexico Chronicles: The Exposición of Don Pedro Bautista Pino 1812; the Ojeada of Lic. Antonio Barreiro 1832; and the additions by Don José Agustín de Escudero, 1849. The part that was quoted in The Catholic World, and from there by Blavatsky, first in Isis Unveiled and then in The Secret Doctrine, is found on p. 29. The phrase in question is not found there. But, we may wonder, could it have been missed in the English translation?

This part is actually by Antonio Barreiro rather than by Don Pedro Bautista Pino. The very rare original 1812 book by Don Pedro Baptista (so spelled on its title page) Pino is reproduced in facsimile in the 1942 book, as is the very rare original 1832 (not 1839) book by Antonio Barreiro. We can there see the original Spanish on pp. 15-16 of Barreiro’s 1832 book, reproduced in facsimile on pp. 277-278 of the 1942 book. The phrase is question is not found there. The whole quotation, in a complete and accurate English translation from p. 29 of the 1942 book, is as follows:

“All of the pueblos have their estufas. This is the name the Indians give to the subterranean rooms that have only one door. There they gather to practice their dances, to celebrate their feasts, and to have their meetings. These estufas are like impenetrable temples, where they gather to discuss mysteriously their misfortunes or good fortunes, their happiness or grief. The doors of the estufas are always closed to us, the Spaniards, as they call us.

“In spite of the dominion held over them by religion, all of these pueblos persist in keeping some of the dogmas which have been transmitted to them traditionally, and which they scrupulously teach their descendants. From this arise the worship they render the sun, the moon, and other celestial bodies, the reverence they have for fire, etc., etc.”

The original Spanish, reproduced on p. 278 of the 1942 book, also ends with etc., etc.:

“. . . el respeto que tienen al fuego &c. &c.”

Not only does Barreiro’s book make no mention of the phrase in question, “whose eggs are called Sibac,” it also makes no mention of “the great snake.” The mention of the great snake comes from a paragraph from a different book, quoted in The Catholic World immediately below the quotation from the Don Pedro Bautista Pino book. This book is there referenced as “Bancroft, Native Races, iii. 173. 174.”; i.e., The Native Races of The Pacific States of North America, by Hubert Howe Bancroft, Volume III: Myths and Languages, London, 1875. This book, too, makes no mention of “whose eggs are called Sibac.” The paragraph that is quoted in The Catholic World, and from there quoted in Isis Unveiled, mistaking it as being from Pino’s 1812 report, says only (Bancroft, pp. 173-174):

“The Pueblo chiefs seem to be at the same time priests; they perform the various simple rites by which the power of the sun and of Montezuma is recognized as well as the power—according to some accounts—of “the Great Snake, to whom by order of Montezuma they are to look for life;” they also officiate in certain ceremonies with which they pray for rain. There are painted representations of the Great Snake, together with that of a misshapen red-haired man declared to stand for Montezuma. Of this last there was also in the year 1845, in the pueblo of Laguna, a rude effigy or idol, intended, apparently, to represent only the head of the deity; it was made of tanned skin in the form of a brimless hat or cylinder open at the bottom.”

Thus the phrase “whose eggs are called Sibac,” found in the quotation given in The Secret Doctrine, is not found in the source it is said to be quoted from, nor in the other source quoted in The Catholic World that Blavatsky mistakenly took as being Pino’s 1812 report.

S.D. vol. 2, p. 222: “All except Xisuthrus and Noah, who are substantially identical with the great Father of the Thlinkithians in the Popol-Vuh, or the sacred book of the Guatemaleans, which also tells of his escaping in a large boat like the Hindu Noah — Vaivasvata.”

Max Müller, p. 338: “The Thlinkithians are one of the four principal races inhabiting Russian America. . . . These Thlinkithians believe in a general flood or deluge, and that men saved themselves in a large floating building.”

As may be seen, Müller’s statements about the Thlinkithians are not from the Popol Vuh. Müller was here bringing in additional material from other sources. The Thlinkithians, now written Tlingits, are Native Americans of coastal Alaska. There is, of course, no reference to them in the Popol Vuh.

The references to the Popol Vuh in The Secret Doctrine, based on Max Müller’s review article, have all been seen to be in some way erroneous. Likewise with the phrase “whose eggs are called Sibac,” which is not found in the source it is referenced to. Besides these, there is one other significant reference to the Popol Vuh in Theosophical writings. The first occurrence of it is in the comments by Aretas, pen name of James Morgan Pryse, on his partial translation of Brasseur de Bourbourg’s French translation. He writes (Lucifer, vol. 15, no. 87, 1894, p. 220):

“Of the seven races of mankind, the first three and one-half are lunar; the last three and one-half are solar. The former are symbolized in Popol Vuh by the men made of red earth, the cork-wood, and the pith of the pliant reed, who are destroyed because they are incapable of invoking Hurakan, the threefold solar fire. From these failures of the third race the monkeys are descendants; . . .”

This pertains to the Theosophical teaching that apes descended from third root-race humanity, rather than humanity descending from the apes. Since there are no apes in the New World, it would not be unreasonable to refer to them as monkeys, which do exist in the New World. But once again the erroneous numbers of the creations, among other things, invalidate this idea. As seen above, in the Popol Vuh the monkeys are remnants of the second attempt at the creation of human beings, not the third. This was the creation of the figure/doll/manikin/effigy people made of wood.

. . . . . . .

The Sources

(listed by date of publication)

The only source of the Quiché (or K’iche’) language Popol Vuh now extant is a copy written in Roman letters, made in the early 1700s CE at Rabinal by Father Francisco Ximénez (said to be in his handwriting by Recinos 1950, p. xii). This manuscript, now held at the Newberry Library in Chicago, includes his Spanish translation. The original is thought to have been written between 1554 and 1558 CE. This original was presumably based on an earlier hieroglyphic Popol Vuh.

An edition of the Spanish translation by Francisco Ximénez, based on an earlier now lost manuscript, was prepared by C. Scherzer and published as:

Las Historias del Origen de los Indios de esta Provincia de Gautemala, Viena [sic], 1857.

French translation, along with the Quiché text:

Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg. Popol-Vuh. Le Livre Sacré et les Mythes de l’Antiquité Américaine, avec les Livres Héroïques et Historiques des Quichés. Paris, 1861.

Brasseur de Bourbourg’s translation was made directly from the Quiché text. The Quiché text did not have divisions, so Brasseur de Bourbourg divided it into four parts, and then each part into several chapters.

Review article on Brasseur de Bourbourg’s 1861 French translation:

Max Müller. “Popol Vuh,” Chapter XIV of his Chips from a German Workshop, vol. 1: Essays on the Science of Religion, London, 1867, pp. 313-340; pp. 332-340 is “Extracts from the ‘Popol Vuh’.”

This review article was written in 1862.

English translation of Brasseur de Bourbourg’s 1861 French translation, partial:

Aretas [pen name of James Morgan Pryse]. “The Book of the Azure Veil,” Lucifer: A Theosophical Magazine, vol. 15, no. 85, Sep. 15, 1894, pp. 41-49 (part 1, chap. 1); vol. 15, no. 86, Oct. 15, 1894, pp. 129-134 (chap. 2); vol. 15, no. 87, Nov. 15, 1894, pp. 220-229 (chaps. 3-5); vol. 15, no. 88, Dec. 15, 1894, pp. 311-316 (chaps. 6-7); vol. 15, no. 89, Jan. 15, 1895, pp. 404-408 (chaps. 8-9); vol. 15, no. 90, Feb. 15, 1895, pp. 478-481 (part 2, chap. 1).

This covers approximately the first fourth of Brasseur de Bourbourg’s 1861 French translation (see pp. 43, 482). It includes some commentary by Aretas regarding it as “a consistent allegory from the first to the last page” “a studied allegory of the secret instructions imparted in the initiation crypts of Central America” (p. 478).

English translation presumably based on and adapted from Brasseur de Bourbourg’s 1861 French translation, complete:

Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie. “The ‘Popol Vuh’ or Book of the Holy Assembly,” The Word: A Monthly Magazine, edited by Harold W. Percival, vol. 2, 1905-1906, pp. 8-23 (Guthrie’s introduction), 77-93 (Guthrie’s introduction, continued), 163-173 (part 1, chaps. 1-3), 224-238 (chaps. 4-9), 297-306 (part 2, chaps. 1-3.22), 369-378 (chaps. 3.23-6); vol. 3, 1906, pp. 41-54 (chaps. 7-11), 104-111 (chaps. 12-14), 167-174 (part 3, chaps. 1-4), 216-230 (chaps. 5-10, part 4, chap. 1-2.19), 302-311 (chaps. 2.20-6.11), 368-370 (chaps. 6.12-7); vol. 4, 1906-1907, pp. 59-61 (chaps. 8-9), 116-124 (chaps. 10-11).

The first part of Guthrie’s Introduction gives an outline of the book, and parallels to other traditions around the world. The second part gives parallels to the Theosophical teachings of the root-races, parallels to the Greek mystery teachings, and parallels of Greek and Quiche names as evidence for the existence of Atlantis. There is no division of parts, chapters, or paragraphs in the original manuscript of the Popol Vuh. Brasseur de Bourbourg divided the text into four numbered parts, and each part into numbered chapters, and each chapter into short paragraphs by indenting them; but he did not number them. Guthrie added numbers to these short paragraphs. Malpas, below, did not add numbers to them.

English translation of Brasseur de Bourbourg’s 1861 French translation, complete:

P. A. Malpas. “The Popol Vuh,” The Theosophical Path, 14 installments from vol. 37, no. 3, March 1930, to vol. 39, no. 4, April 1931. These are: vol. 37.3, pp. 200-213 (Malpas’s introduction, and part 1, chaps. 1-3), 37.4, pp. 322-328 (chaps. 4-7), 37.5, pp. 424-432 (chaps. 8-9, part 2, chaps. 1-2 partial), 37.6, pp. 522-531 (chaps. 2-5); vol. 38.1, pp. 73-81 (chaps. 6-8), 38.2, pp. 177-184 (chaps. 9-11), 38.3, pp. 271-276 (chaps. 12-13), 38.4, pp. 354-362 (chap. 14, part 3, chaps. 1-4), 38.5, pp. 448-457 (chaps. 5-9), 38.6, pp. 544-550 (chap. 10, part 4, chaps. 1-2); vol. 39.1, pp. 82-91 (chaps. 3-6), 39.2, pp. 138-145 (chaps. 7-9), 39.3, pp. 265-271 (chaps. 10-11 partial), 39.4, pp. 360-364 (chaps. 11-12).

The introduction by Malpas provides historical background for the Popol Vuh and its French translation. He notes that at the time Brasseur de Bourbourg translated the Popul Vuh he regarded it as containing historical records. But several years later he came to regard it as containing symbolism, at which time he began putting forward views supporting the existence of Atlantis as the land from which the Maya people came. This resulted in a loss of estimation in the eyes of the world. Malpas ends with a biographical sketch of Brasseur de Bourbourg and a brief survey of his writings. As for the translation, Malpas writes (p. 203) that Brasseur de Bourbourg “attempted no elegance of diction or style, because he desired to make it as literal a translation as possible. In translating his version into English we have followed the same plan.”

English translation of Spanish translation made directly from the Quiché text:

Adrián Recinos, Spanish translation, translated into English by Delia Goetz and Sylvanus G. Morley. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiche Maya. University of Oklahoma Press, 1950.

This is the first complete English translation of the Popol Vuh to become available in book form. It was made from the 1947 Spanish translation by Adrián Recinos, which was made directly from the Quiché. It has a lengthy Introduction, providing comprehensive information about the history of the text of the Popol Vuh, its manuscript and related books and materials. There are many excerpts from Spanish language sources that are very old and difficult to access. As for the translation, Recinos wrote (p. xiii): “Comparing the original text transcribed by Ximénez with the text published by Brasseur de Bourbourg, I noticed some differences, important omissions, and other changes which affect the interpretation of the Quiché document. Furthermore, the possibility of clarifying and correcting passages in the existing translations stimulated my desire to undertake a new version direct from the original Quiché into Spanish.”

First English translation made directly from the Quiché text:

Munro S. Edmonson. The Book of Counsel: The Popol Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University, New Orleans,1971.

Edmonson was not only the first to translate the Popol Vuh into English directly from the Quiché, but also the first translator of the Popol Vuh to treat it as being entirely written in poetry, in parallelistic couplets. His translation is formatted accordingly, as is the Quiché text, which he includes in facing columns. His Quiche-English Dictionary had been published earlier, in 1965. Besides this, for his translation he consulted the eleven previous translations that were made more or less directly from the Quiché: in Spanish (Ximénex 1703?, Villacorta and Rodas 1927, Recinos 1947 and 1953, Burgess and Xec 1955, Villacorta 1962), French (Brasseur de Bourbourg 1861, Raynaud 1925), German (Pohorilles 1913, Schultze-Jena 1944, Cordan 1962), and Russian (Kinzhalov 1959). He drew upon all of them in his notes, and he described each of their approaches in his Introduction (ix-xi). He wrote (p. xi) “The Popol Vuh is in poetry, and cannot be accurately understood in prose.” “That I have ventured to attempt a twelfth translation is largely owing to the failure of the previous versions to deal accurately with its major stylistic feature.”

Second English translation made directly from the Quiché text:

Dennis Tedlock. Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, New York, 1985.

Revised edition, Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life, New York, 1996.

This translation is formatted to be user friendly to those who only wish to read the text, without notes. So the unencumbered translation is given first. All the notes, about a hundred pages of them in smaller type, are given separately in the latter part of the book. The revised edition is a major revision, as Tedlock explains in his new Preface. It also has the notes at the back. Although the Quiché language is still spoken by large numbers of people, the Popol Vuh has long been lost to the Quiché people. Tedlock showed the text of the Popol Vuh to a Quiché “daykeeper,” a diviner, whom he had befriended and with whom he had apprenticed as a daykeeper. This man, Andrés Xiloj, agreed to go through the text with Tedlock. Tedlock wrote (1985, p. 16): “In the present volume the effects of the three-way dialogue among Andrés Xiloj, the Popol Vuh text, and myself are most obvious in the Glossary and the Notes and Comments, but they are also present in the Introduction and throughout the translation of the Popol Vuh itself.”

Third English translation made directly from the Quiché text:

Allen J. Christenson. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya, O Books, U.K., 2003;

Vol. 2: Literal Poetic Version: Translation and Transcription, 2004.

Reprint: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007-2008.

Christenson had learned to speak Quiché when working as a volunteer after the 1976 earthquake in Guatemala. A couple years later he began working on a Quiché dictionary and grammar at Brigham Young University. Back in Guatemala he trained as a daykeeper. He wrote that the first volume of his translation (p. 23): “aimed at elucidating the meaning of the text in light of contemporary highland Maya speech and practices, as well as current scholarship in Maya linguistics, archaeology, ethnography, and art historical iconography.” His second volume is a major study tool. Not only does it give a literal word for word translation and the facing Quiché text, but it also carefully formats both to reflect the Quiché poetic structure. Edmonson was the first to give the text in parallel couplets in his translation, as a necessary aid to their comprehension. Since his time additional poetic structures, not only parallel couplets, have been recognized in the Quiché text. Christenson’s formatting in this volume shows these.

Category: Anthropogenesis, Creation Stories, Uncategorized |