The Sāṃkhya teachings are regarded in Indian tradition as the oldest system of philosophical thought, the original worldview, darśana, and their promulgator, Kapila, is regarded as the first knower, ādi-vidvān. Kapila, using an emanated mind, nirmāṇa-citta, gave the teachings to his pupil, Āsuri, who in turn gave them to his pupil, Pañcaśikha. Pañcaśikha then systematized the teachings, referred to as tantra, into sixty topics, and wrote them down in a book, the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra, the “Sixty Topics of the Teachings.” This book is long lost, but a small number of fragments from it have been quoted in other early books. One of these fragments, very little known, speaks of primordial darkness, tamas, just like the famous Ṛg-veda hymn 10.129 does, and just like the “Book of Dzyan” does.

The Sanskrit fragments attributed to Pañcaśikha were first collected by Fitz-Edward Hall in his Preface to his 1862 edition of the Sānkhya-Sāra (pp. 21-25, footnotes). He found twelve of these in Vyāsa’s Yoga-sūtra-bhāṣya that were specifically attributed to Pañcaśikha by the sub-commentators Vācaspati Miśra, Vijñāna Bhikṣu, or Nāgojī Bhaṭṭa. These twelve were then translated into German by Richard Garbe in an 1893 article, to which he added a reference to another fragment quoted in Vijñāna Bhikṣu’s commentary on Sāṃkhya-sūtra 1.127. Nine more from the Yoga-sūtra-bhāṣya were added to these twelve in a 1912 publication by Rāja Rāma, making twenty-one. However, these nine are not attributed to Pañcaśikha by any classical writer. Other than one attributed to Vārṣagaṇya, their authorship is unknown. Similarly, Hariharānanda Āraṇya also added nine more from the Yoga-sūtra-bhāṣya to these twelve, one of which, a Vedic fragment, is not among the nine added by Rāja Rāma. Nandalal Sinha published all twenty-two of these as an appendix in his 1915 book, The Samkhya Philosophy, noting that beyond the first twelve, “we do not feel we should be justified in affiliating these aphorisms to Pañchaśikha” (p.18). Additional fragments from three commentaries on the Sāṃkhya-kārikā, namely, the Yukti-dīpikā, the Māṭhara-vṛtti, and the Gauḍapāda-bhāṣya, were collected by Udayavīra Śāstri and published in his 1950 Hindi book, Sāṃkhyadarśana kā Itihāsa. These, along with twenty-one fragments from the Yoga-sūtra-bhāṣya accepted by previous writers, were given in a list of thirty-six fragments by Janārdanaśāstri Pāndeya in his 1989 Sanskrit book, Sāṃkhyadarṣanam. It is only these last two sources that include the fragment on primordial darkness, tamas.1

The Sāṃkhya-kārikā purports to summarize the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra in a mere seventy verses. There are five very old commentaries on the Sāṃkhya-kārikā. These are the Gauḍapāda-bhāṣya, first published in 1837, the Māṭhara-vṛtti, first published in 1922, the Sāṃkhya-saptati-vṛtti, published in 1973, the Sāṃkhya-vṛtti, published in 1973, and the Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā, whose French translation was published in 1904.2 The Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā is not available in its original Sanskrit, but only in its Chinese translation made in the sixth century C.E. by Paramārtha and found in the Chinese Tripiṭaka. These five commentaries are so similar that they led to much discussion as to which copied which. However, the more obvious answer is that they all drew upon the now lost Ṣaṣṭi-tantra in their explanations of the Sāṃkhya-kārikā, which purports to summarize the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra. Three of these give the fragment on primordial darkness, tamas, in their commentary on verse 70. These are the Māṭhara-vṛtti, the Sāṃkhya-saptati-vṛtti, and the Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā. The Gauḍapāda-bhāṣya ends at verse 69, so does not comment on verse 70, and the Sāṃkhya-vṛtti manuscript omits many lines through scribal error, so probably had the fragment on primordial darkness. Another commentary on the Sāṃkhya-kārikā, of unknown age, is the Jaya-maṅgala, which was first published in 1926. It, too, gives the fragment on primordial darkness. This fragment is attributed to the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra written by Pañcaśikha. Both the Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā and the Jaya-maṅgala attribute this quote directly to Kapila, the founder of the Sāṃkhya teachings, who taught it to Āsuri, who in turn taught it to Pañcaśikha, who wrote it down in the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra. The Māṭhara-vṛtti and the Sāṃkhya-saptati-vṛtti give this quote to define the teaching, tantra, the Sāṃkhya teaching of Kapila that Pañcaśikha elaborated in the sixty topics of the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra.

Sāṃkhya-kārikā, verses 69-70:

puruṣārtha-jñānam idaṃ guhyaṃ paramarṣiṇā samākhyātam |

sthity-utpatti-pralayāś cintyante yatra bhūtānām || 69 ||

“This secret knowledge of the purpose of the puruṣa, in which the abiding, arising, and dissolution of beings is described, was fully made known by the great seer [Kapila].

etat pavitryam agryaṃ munir āsuraye ‘nukampayā pradadau |

āsurir api pañcaśikhāya tena ca bahulīkṛtaṃ tantram || 70 ||

“This purifying foremost [knowledge] the muni [Kapila] out of compassion gave to Āsuri. Āsuri in turn [gave it] to Pañcaśikha, and by him the teaching was made extensive.”

The Pañcaśikha quote as found in the Māthara-vṛtti commentary on verse 70 (1922, p. 83):

tama eva khalv idam agra āsīt | tasmiṃs tamasi kṣetrajño ‘bhivartate prathamam |

The Pañcaśikha quote as found in the Sāṃkhya-saptati-vṛtti commentary on verse 70 (1973, p. 79):

tamaiva khalv idam agryam āsīt | tasmin tamasi kṣetrajñaḥ prathamo ‘sya[bhya]vartata iti |

The Pañcaśikha quote as found in the Jaya-maṅgala commentary on verse 70 (1926, p. 68):

tama eva khalv idam āsīt | tasmiṃs tamasi kṣetrajña eva prathamaḥ |

The Pañcaśikha quote as found in the Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā commentary on verse 70, as re-translated into Sanskrit from Chinese by N. Aiyaswami Sastri (1944, p. 98):

tama eva khalv idam agra āsīt | tasmin tamasi kṣetrajño ‘vartata |

Translation of the Pañcaśikha quote:

“In the beginning (agre) this (idam) was (āsīt) darkness (tamas) alone (eva). In that (tasmin) darkness (tamasi ) the knower of the field (kṣetrajña) arose (abhivartate, abhyavartata, avartata) first (prathama).”

Compare “Book of Dzyan,” stanza 1, verse 5:

“Darkness alone filled the boundless all, . . .”;

Compare Ṛg-veda hymn 10.129, verse 3a:

táma āsīt támasā gūḷhám ágre

“Darkness was hidden by darkness in the beginning.”

The comments on the Pañcaśikha quote from the Sāṃkhya commentaries:

tama iti ucyate prakṛtiḥ, puruṣaḥ kṣetrajñaḥ |

tama iti ucyate prakṛtiḥ | kṣetrajñaḥ puruṣaḥ |

“Darkness is called prakṛti; the knower of the field is puruṣa.” (Māṭhara-vṛtti and Sāṃkhya-saptati-vṛtti ).

tamaḥ pradhānam, kṣetrajñaḥ puruṣa ucyate |

“Darkness is pradhāna. The knower of the field is called puruṣa.” (Jayamaṅgala).

kṣetrajñaḥ puruṣaḥ |

“The knower of the field is puruṣa.” (Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā).

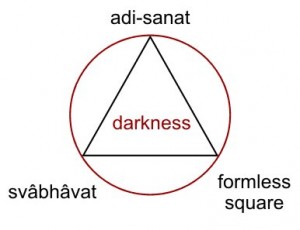

In the standard accounts of Sāṃkhya there is no mention of the idea that the “knower of the field,” i.e., puruṣa, “spirit,” arose in primordial “darkness,” i.e., pradhāna or prakṛti, “primary substance.” Such a teaching is quite absent in the standard Sāṃkhya teachings. On the contrary, pradhāna or prakṛti is routinely subordinated to puruṣa; put crudely, matter is subordinated to spirit. In the great Vedānta teachings, which completely eclipsed the Sāṃkhya teachings in India, the absolute brahman is defined as “pure consciousness” or “only consciousness” (cin-mātra). Indeed, Śaṅkarācārya in his most definitive work, his Brahma-sūtra-bhāṣya, takes Sāṃkhya as his primary opponent, and refutes it on the basis of the premise that the absolute cannot be unconscious, as pradhāna or prakṛti is.

The original Sāṃkhya teaching found in this Pañcaśikha quote, of a primordial darkness in which the conscious puruṣa arose, but which itself is not conscious, finds an exact parallel in the Theosophical teaching of a primordial darkness, in which during pralaya, the night of the universe, “life pulsated unconscious” (“Book of Dzyan,” stanza 1, verse 8).3

Notes:

1. The writers who gathered these fragments assumed that Pañcaśikha wrote the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra, in accordance with what is said in the Sāṃkhya-kārika, verses 70-72, and the commentaries thereon. However, other fragments from the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra are attributed to Vṛṣagaṇa or Vārṣagaṇya. This has led researchers such as G. Oberhammer to conclude that all of the fragments attributed to Pañcaśikha are actually from the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra written by Vṛṣagaṇa. See his 1960 article, “The Authorship of the Ṣaṣṭitantram.” Of course, this does not rule out the possibility of an original Ṣaṣṭi-tantra written by Pañcaśikha, and another later one written by Vṛṣagaṇa. Perhaps most of the known fragments do indeed come from the one written by Vṛṣagaṇa, since in most cases the authorities attributing them to Pañcaśikha are not ancient. In the case of the fragment on primordial darkness, however, we have four old authorities agreeing that it comes from the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra written by Pañcaśikha. For examples of the fragments from the Ṣaṣṭi-tantra that are in some cases attributed to Vṛṣagaṇa or Vārṣagaṇya, see the 1999 article by Ernst Steinkellner, “The Ṣaṣṭitantra on Perception, a Collection of Fragments.” These were elaborated in his 2017 book, Early Indian Epistemology and Logic: Fragments from Jinendrabuddhi’s Pramāṇasamuccayaṭīkā 1 and 2.

2. All these books are posted here with the Sanskrit Hindu Texts, including a 1932 English translation of the 1904 French translation of the Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā, as well as a 1944 re-translation of it back into Sanskrit directly from the early Chinese translation.

3. In the commentary preceding this Pañcaśikha quote, the Suvarṇa-saptati-vyākhyā says that this secret knowledge taught by Kapila was established before the four Vedas arose. The Theosophical teachings, too, say about its secret doctrine “that its teachings antedate the Vedas.” (The Secret Doctrine, vol. 1, p. xxxvii).

Category: Darkness, Uncategorized | 1 comment