1. Why would we want to know the orthography of dgyu?

On the one hand the term fohat is the most enigmatic of the technical terms used in The Secret Doctrine (SD), and on the other, it is crucial to the esoteric philosophy presented in the work. There are only a few locations in the SD where fohat is unambiguously connected to other concepts, one of which is in SD I, 31 (stanza V, śloka 2):

[…] THE DZYU BECOMES FOHAT […]

This is a strong statement, most probably referring to the moment when the universe is evolving from the state of pralaya, where fohat is connected to “THE DZYU”, as it is spelled in the SD. Defining this concept DZYU, or dgyu as it is spelled in another location, would take us very close to exactly defining and understanding the mysterious concept of fohat and its workings.

2. How does HPB describe dgyu?

The only location in the SD where dgyu is described, is SD I, 108, where HPB comments on stanza V, śloka 2:

Dzyu is the one real (magical) knowledge, or Occult Wisdom; which, dealing with eternal truths and primal causes, becomes almost omnipotence when applied in the right direction. Its antithesis is Dzyu-mi, that which deals with illusions and false appearances only, as in our exoteric modern sciences. In this case, Dzyu is the expression of the collective Wisdom of the Dhyani-Buddhas.

The term dgyu is not found in the TG. In the Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary published by the Theosophical University Press, Dzyu is identified as a Senzar word, referring to SD I, 108, but there is no clue to be found in HPB’s writings to indicate that it would be indeed Senzar.

3. Cosmological Notes

Prior to 1885 the term fohat was not used in theosophical literature. The oldest document in which it was used are the “Cosmological Notes”, containing written instructions from Mahātma M. to A.O. Hume, handed down to us by A.P. Sinnett, and published both in ETM and BL. In the Cosmological Notes (BL p. 376) we find a similar affirmation as in SD I, stanza V, śloka 2:

Dgyu becomes Fohat when in its activity – active agent of will – electricity – no other name.

All technical terms in the Notes seem to be Sanskrit or Tibetan, so we might assume that Dgyu is also a Tibetan, as it has a structure looking like a Tibetan syllable.

An interesting detail in the manuscript of the Cosmological Notes is the fact that the first time they are mentioned, the terms dgyu and dgyu mi both carry an umlaut (Dgyü). In ML 35 (written by KH), dgyu is spelled as dgiü, also with umlaut.

4. The Syllable Dgyu: the Rime

The IPA /y/ sound in standard Tibetan is only realised when a syllable ends in -ud or -us. This would narrow down considerably the possibilities for the orthography of dgyu.

Some of the umlauts in the text seem to have been added later, perhaps at the same time the annotations were interscribed, including the underlined title “Appendix II” on top of page 2. The annotations do not seem to be in the same handwriting as the original notes. Compare for example, the capital A of the word Appendix with the capital A’s in the manuscript text. In The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to A.P. Sinnett (BL) the Notes appear as Appendix II. It is therefore entirely possible that the annotations and also the umlauts are the handwriting of the transcriber/compiler of the book, A.T. Barker. This would be consistent with the spelling in the ML edited by Barker. The umlauts on Dgyü and Dgyü Mi however, are not reproduced in BL. In Jinarajadasa’s edition (ETM) of the Notes, the umlauts are absent as well.

5. The Syllable Dgyu: the Onset

In Jinarajadasa’s edition, a remark of Sinnett is added, telling that M. himself “wrote out” the table of correspondences between Man and Universe. This means that Sinnet has copied the table from the handwriting of M., instead of interpreting the words from hearing. Interestingly, in the table, Linga Sharira is called Ling Sharir in line 3, we also have Bhut, Purush, Brahm, dropping the final a’s, as in the Sanskrit pronounciation typical of speakers of modern Hindi. Apparently M’s concern was that the words were written as they were pronounced, as opposed to how they were written in the original language. The rendering of the Tibetan terms is therefore presumably also a phonetic transcription for an English target audience.

In that case, the d in dgyu could not have been a silent letter. Also, English has two sounds associated with the letter g (besides /ŋ/ in “thing”), the plosive /g/ and the affricate /dʒ/. The dg-combination does not exist with a plosive /g/-sound in English, so our dgy-combination would probably be the affricate /dʒ/, the g-sound in “gin”, or something close to it. This is consistent with HPB’s spelling DZYU, for example in SD I, 108. The /dʒ/, and phonemes very close to it, are listed in the following table.

Possible phonemes for the onset, and their Tibetan Wylie transliteration, in approximate order of distance from /dʒ/:

6. Dictionaries

Combining the ideas on onset and rime, we could try finding some matching candidates for dgyu, using a lexicon. In the following table all combinations are summed up, with the entries found in common dictionaries marked bold.

|

|

|

-ud |

-us |

|

1 |

pya, bya, … |

pyud, byud, … |

pyus, byus, … |

|

2 |

mja, ‘ja |

mjud, ‘jud |

mjus, ‘jus |

|

3 |

ra |

rud |

rus |

|

4 |

‘dra, ‘gra, … |

‘drud, ‘grud, … |

‘drus, ‘grus, … |

|

5 |

‘gya |

‘gyud |

‘gyus |

|

6 |

brgya, bsgya, dgya, bgya, rgya, sgya, … |

brgyud, bsgyud, dgyud, bgyud, rgyud, sgyud, … |

brgyus, bsgyus, dgyus, bgyus, rgyus, sgyus, … |

|

7 |

gya |

gyud |

gyus |

Elements we may look for in the translation are “real (magical) knowledge, dealing with eternal truths and primal causes” (SD I, 108), and the negation dgyu mi, or min or med, “illusion and false appearances only” (SD I, 108).

One of the most valued translators of Tibetan to English is Jeffrey Hopkins, who prepared a Tibetan-Sanskrit-English Dictionary, which was also published in digital form by the Dharma Drum Buddhist College in Taipei in 2011.

a. Under rus we find there:

b. Under ‘grus we find:

(translation-eng) {Hopkins} zeal; enthusiasm; diligence

c. Under brgyud pa we find:

ṃ

parā

ṃ

parā

d. Under rgyud we find:

ṃ

tāna

ṃ

tati

ṃ

śa

e. Under rgyus we find:

In the older dictionary of Jäschke (1881) the lemma rgyus first refers to rgyu, and secondly gives “notice, intelligence, knowledge”. Rgyus is the instrumental case of rgyu: cause, or because.

Under rgyu we find:

ṇ

a

ṣ

ad

ṃ

nidānam

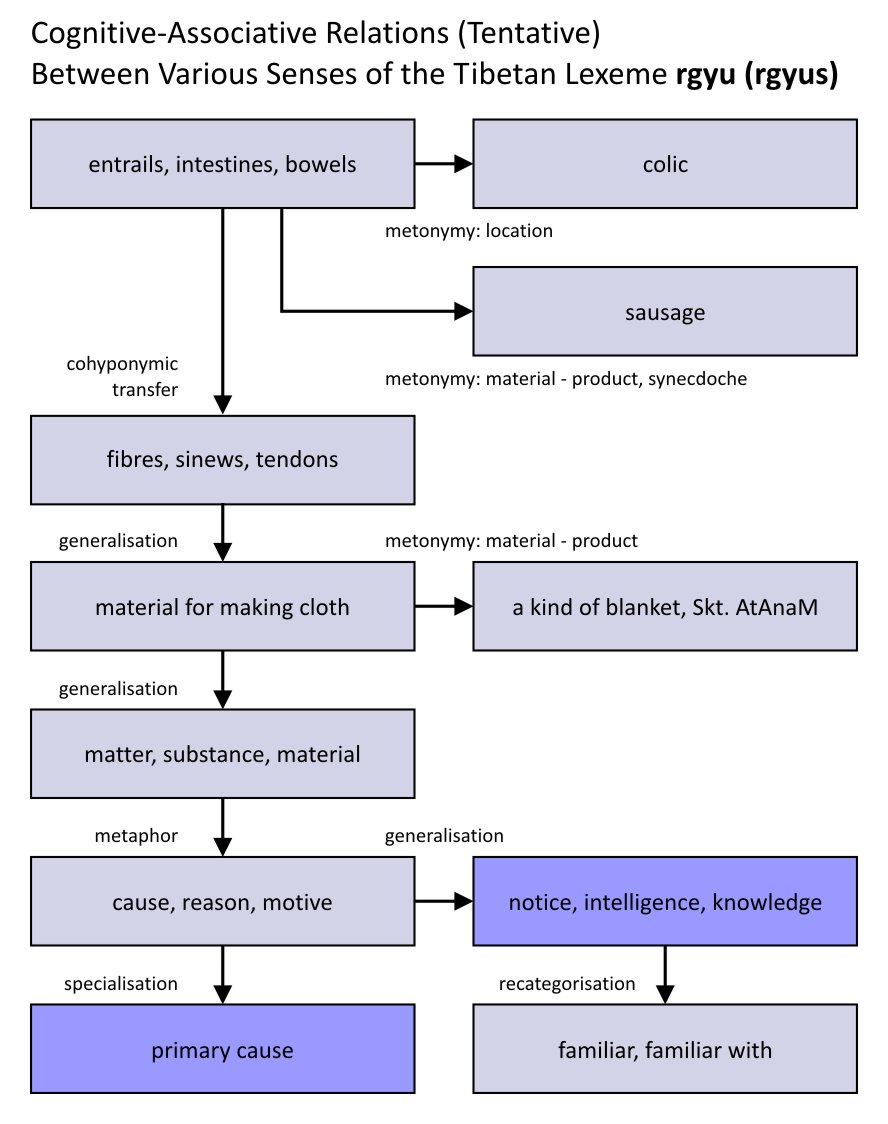

Literature used in preparing the diagram

1. Joachim Grzega, Bezeichnungswandel: Wie Warum, Wozu?, Winter, Heidelberg, 2004

2. Andreas Blank, Prinzipien des Lexikalischen Bedeutungswandels am Beispiel der romanischen Sprachen, Max Niemeyer, Tübingen, 1997

3. Tibetan and related dictionaries: Conze (1973), Das (1902), Jäschke (1881), Hopkins (2011), Mahavyutpatti (nos. 7625, 7199), Matisoff (STEDT, online), Rangjung Yeshe (online), Starostin (Starling, online), etc.

7. Orthography

Of the matching Tibetan terms, rgyus might be a realistic candidate for dgyu, fitting HPB’s description in the sense that we find the two elements of “knowledge” and “primal causes” from the description in SD I, 108 associated with the term rgyu, which is, in its turn, closely related to rgyus. The spelling dgyü, with an umlaut, following A.T. Barker, would then be justified.

In an earlier post entitled “Kāraṇa, the Causeless Cause” we have argued that dgyu being the (manifested) “propelling force” which “sets in motion the law of Cosmic Evolution”, is kāraṇa, the “force” resulting in cosmic motion, or the principle of abstract motion. (cp. SD I, 109-110) In Hopkins’ dictionary we find nidāna under rgyus, a term which is used by HPB as a synonym for kāraṇa, and the term kāraṇa itself under rgyu.