1. What is so interesting about the Ratnagotravibhāga?

In the process of writing The Secret Doctrine, HPB started out writing a short history of occultism to show that that in different times a “universal secret doctrine” was known to many “philosophers and initiates”, and to describe the mysteries and some rites. This became a “large introductory volume”, and in a second and third volume, she described the evolution of cosmos and man respectively. In a letter to A.P. Sinnett (BL p. 195, letter LXXX dated March 3, 1886) she wrote that every section of the book started with a page of translation from the Book of Dzyan and the Secret Book of “Maytreya Buddha”. The initial “first” volume was not published until 1893, after HPB’s death, as a third volume to The Secret Doctrine, but in that volume there are also no translations to be found from this Secret Book of “Maytreya Buddha”. In the final 1888 version of The Secret Doctrine, we find indeed fragments from the Book of Dzyan, but not from the Secret Book of “Maytreya Buddha”.

From the letter to Sinnett we can derive that the Secret Book of “Maytreya Buddha” is an unknown version of the so-called “five books of Maitreya”. One of the known “five books” of Maitreya is the Ratnagotravibhāga (RGV), otherwise known as the Uttaratantra. Finding a reference to any of these five books would be interesting since at some point during the conception of The Secret Doctrine apparently the Mahātmas found the secret versions of these books of similar importance as a source for The Secret Doctrine (SD) as the Book of Dzyan itself.

2. A description of KH’s note

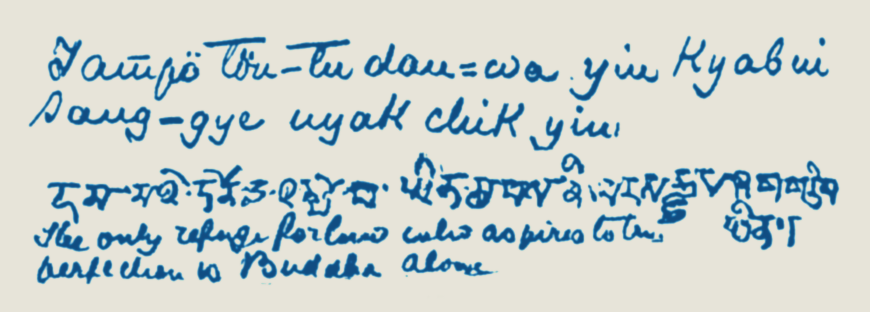

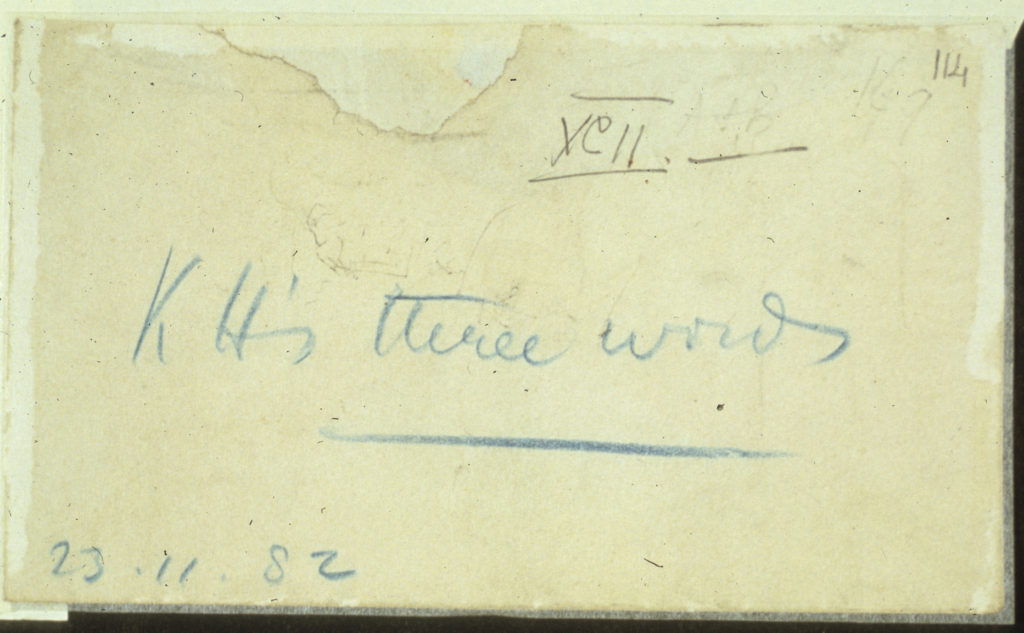

In the collection of Western Manuscripts in the British Library, in the seventh and last volume of the “Mahatma Papers” (Add MS 45289 B) we find a small note, folio number 268b, which was, according to A. Trevor Barker (ML p. xlvii), enclosed together with Mahātma Letter number XCII (96). (The Barker number is set in Roman style, followed by the chronological number of Vic Hao Chin Jr. in Arabic style between parentheses.) In their work Blavatsky’s Secret Books (p. 106), David and Nancy Reigle describe the text as a quotation from the Ratnagotravibhāga (RGV chapter I verse 21), identified as such by the Venerable Professor Samdhong Rinpoche. This is an colour impression of the note on the basis of ML p. xlvii:

The size is about 3-3.5 cm (1.25″) high, and 11.5 cm (4.5″) wide. At the bottom it is cut off with scissors or a sharp knife. The paper looks like part of an envelope. The verso side shows a monogram BLR or BRL on top of a ribbon bearing the appropriate text “Knowledge is power”, perhaps the logo of the paper or envelope manufacturer. Thin rice paper or librarian’s tape is attached to it. The paper was folded in three after it was cut off. It was written on after it was cut off.

The first line is unmistakably in KH’s “large script” handwriting. There is a horizontal line in the middle from left to right, which is part of the note, in blue pencil. Note that this line is not reproduced in the image, above.

Moreover, in ML (p. xlvii), Barker mentions that the note was enclosed with letter XCII (96), but in the manuscript book in the British Library there is an envelope with the note having folio numbers 268a and 268b, suggesting that the note was in a separate envelope. These folio numbers were assigned by a library employee at a later date. It is therefore unclear what was in envelope 268a.

The note shows three different scripts:

- The first script is in KH’s handwriting, in blue pencil. The two lines are a phonetic rendering of the second line, which is in Tibetan.

- The second script is Tibetan dbu can script. dBu can is not so much used for handwriting, as it is for printing or artwork. It is written in an uncoordinated manner, as if by someone who did not use this script on a daily basis. Perhaps the line was copied from a dpe cha leaf.

- The third is a small roman script handwriting, representing an English translation of the second line. Although the last line is written in the same pencil colour as the other lines, comparison shows that the third line is not the same handwriting. It could perhaps be KH’s, but it is very different from the script used in the top line. It is definitely not HPB’s or Sinnett’s.

Transcribing the three lines, we have:

1. Tampö tön-tu dau = wa yin Kyab ni Sang-gye nyag chik yin

3. The only refuge for him who aspires to true perfection is Buddha alone

3. Analysis of the Tibetan text

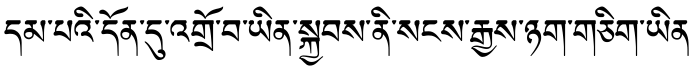

Comparing the Tibetan line with the Tibetan version of the RGV, we can see one difference: the first “yin” is rendered “yi” in the RGV. A Wylie transliteration from the RGV in I.21 would be:

dam pa’i don du ‘gro ba yi, , skyabs ni sangs rgyas nyag gcig yin, ,

An English translation of the RGV from Tibetan by Eugene Obermiller has been published in 1931 (The Sublime Science […], Acta Orientalia IX, pp. 81-306):

In the absolute sense, the refuge

Of all living beings is only the Buddha.

This translation is not exactly the same as the one in KH’s note. Interestingly the main difference is in the phrase ‘gro ba yin, translated as “for him who aspires”. On the basis of ‘gro ba yi, instead of ‘gro ba yin, the most obvious translation would be “of living beings”. The primary meaning of ‘gro ba is “going” or “moving”, and from there the meaning of living or transmigrating beings is derived.

In 1935 and 1937, the discovery by the famous Rahul Sāṃkṛtyāyan of two partial Sanskrit manuscripts of the RGV was made public.

Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society, vols. XXI, p. 31 (III. Ṣalu monastery, vol. XI-5, No. 43) and XXIII, p. 34 (VII. Ṣalu monastery, vol. XIII-5, No. 242):

No. 43 Mahāyānottaratantra (author “Maitreyanātha”) in Śāradā script, 202/3×21/3 ‘, Incomplete

No. 242 Mahāyānottaratantra-ṭīkā (author “Asaṅga”?) in Māgadhī script 121/2×17/8 ‘, 54 leaves, Incomplete

In Sanskrit, the first half of verse I.21 is:

jagaccharaṇamekatra buddhatvaṃ pāramārthikam /

We might translate this as:

Ultimately, Buddhahood is the only refuge of living (transmigrating) beings,

where the Sanskrit equivalent of ‘gro ba is jagat, derived from the root gam, “to go”, and also meaning “that which is alive”, “living beings”, “the world”.

Perhaps there is a Tibetan manuscript of the RGV to be found, or a Tanjur edition, where the phrase ‘gro ba yin is erroneously used instead of ‘gro ba yi.

The transcription at the beginning of the note may be used to find an indication for the Tibetan dialect used. At first sight it looks like Central Tibetan, the dialect of the province of dbus gcang, which in the present time could be considered “standard Tibetan”.

4. The circumstances of letter XCII (96)

The text “KH’s three words” on the envelope of letter XCII (96) is not in KH’s typical handwriting. If KH would have written this, it would have been strange that he addresses himself in the third person. It is similar to Sinnett’s handwriting, therefore the date on the envelope, November 23, 1882, may represent the date of reception.

In the chronological edition on p. 335, Vicente Hao Chin Jr. tells us that in November 1882, Sinnett was given notice of termination of his services as editor of The Pioneer. This corresponds to p. 34 of Sinnett’s autobiography, published in 1986. In the chronology in the Readers’ Guide to the Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett (Linton and Hanson, 2nd ed. 1988, note: this chronology is different from the 1st ed. 1972), we can see that on March 30, 1883, the Sinnetts set sail for England.

In the letter XCII (96) itself, three passwords are given for the purpose of being able to authenticate future communication with the Mahātmas, and it is mentioned that Sinnett would need the passwords in London. This means that on November 23, 1882, it was known to KH that Sinnett would go to London.

Letter XCII (96) is actually only a postscript to letter LXXII (95). Of this letter it is also unclear when exactly it was received, but it is plausible that it was received in November 1882.

According to the “Reader’s Guide” it was received in (early) November 1882. According to Margaret Conger in the “Combined Chronology”, it was received in Allahabad in March 1882. However in the letter is spoken of a meeting which was held in December 1882, which makes it more likely that it was sent in November. Further, the envelope of the postscript is dated November 23, and there many other letters sent from KH to Sinnett from March to November. In this case it would have been a postscript to letter XCI. The KH-letters received by Sinnett in November were according to Conger: CXIX (ML p. 451), LXXIX (ML p. 382) (>= Nov. 17th), LXXX (ML p. 383) (>= Nov. 17th), XCIa (ML p. 415), XCIb (ML p. 416), and XCII (ML p. 419). In the chronological numbering only letters 95 (Barker LXXII) and 96 (Barker XCII) were received in November. This seems quite a difference! I have not taken the time to investigate this further.

Why was letter XCII (96) sent as a postscript and not as a separate letter? Letter LXXII (95) does not reflect the knowledge of Sinnett’s imminent leaving for England. The postscript mentions: “be prepared for it [that is forging of the handwritings of the Mahātmas] in London”. The topic of the letter, what went on in the lodge in Allahabad, has now become less relevant for Sinnett, because he has decided to leave India. We can imagine therefore, that the information of Sinnett’s leaving has reached KH just after he wrote the letter, prompting the need for a postscript.

Why was the note written, and why was it sent to Sinnett in the envelope of letter XCII? It was written because the author, KH, had this text in written Tibetan and wished to know for himself or someone else how it was pronounced, perhaps to memorise it or use as a mantra. The note was sent, most probably by KH, to be of use to Sinnett. It was already clear to KH that their relationship would change drastically when Sinnett would move to London. It seems that sending this line from the RGV is a gesture, a token of sympathy and brotherly support. We can use this text ourselves as a mantra for the purpose of realising the quality of taking refuge in only in the ultimate truth.

Epilogue: more on KH’s note

Antonios Goyios has discovered that the Tibetan phrase is taken not from the Tanjur, but from a Western book, A Manual of Tibetan, written by T.H. Lewin, published in 1879 in Calcutta. Goyios published his discovery already in his 2009 article entitled Tracing the Source of Tibetan Phrases Found in Mahatma Letters #54 and #92 to be found on Daniel Caldwell’s web site “Blavatsky Archives”:

http://blavatskyarchives.com/kammitshar/kammitshar.htm

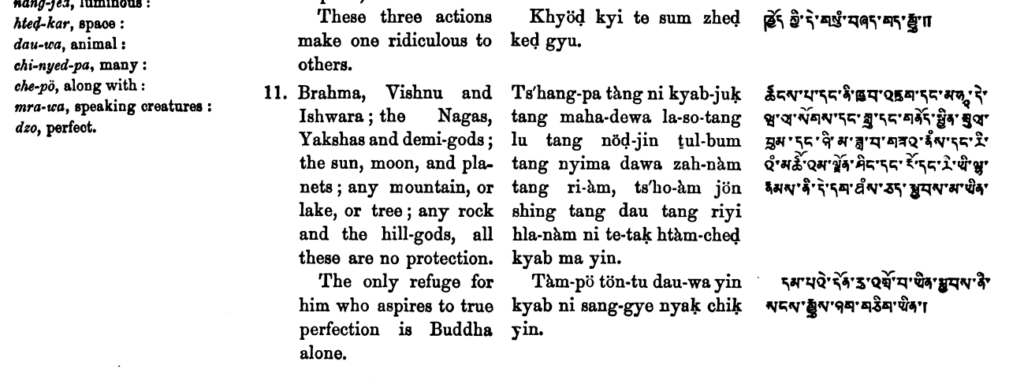

On p. 134 of A Manual of Tibetan (exercise 97, example 11) we find the following:

For our “Tampö tön-tu dau = wa yin Kyab ni Sang-gye nyag chik yin” we find “Tàm-pö tön-tu dau-wa yin kyab ni sang-gye nyaḳ chiḳ yin”, which is close. In the margin, the words newly introduced are listed, and dau-wa (‘gro ba) is listed as “animal”, which is not found in the translation. The Tibetan text as well as the transcription have yin instead of yi.

In a footnote Goyios remarks: “It should perhaps be noted at this point that the part of example 11 preceding the quotation found on Mahatma letter #92, although apparently in mutual context with it’s latter part (which seems like a natural continuation), is not to be found in the vicinity of Ratna-gotra-vibhaga, chapter 1, verse 21 (or 20). Whether it is to be found in another part of the same work remains to be known, although it appears that example 11 as found in “Manual of Tibetan” is a compilation from more than one particular source.”

It may also be interesting to know that the lama who cooperated in making the Manual, came from the monastery of “Pemiongchi”, or Pema Yangtse (pa dma yang rtse), which is located in Sikkim, not too far North of Darjeeling. (at 27°18’19”.00 N 88°15’6″.87 E) HPB had met KH in Sikkim early November. She was staying in Darjeeling, and they had met in Phari Dzong (phag ri, around 29°45′ N 89° 10’ E), again, not too far from Darjeeling and Pema Yangtse, across the border in Tibet. (103 km/64 miles as the crow flies) Still the line is very beautiful and can be used as a mantra, albeit not one directly from the Ratnagotravibhāga, but from A Manual of Tibetan… •

Attachment

Category: Five Books of Maitreya, Mahatma Letters, Ratnagotravibhaga | 3 comments