There was much interest in the Kālacakra-tantra when it appeared in India about a thousand years ago. So when it was brought to Tibet a short time later, it was translated from Sanskrit into Tibetan several times. The translation that would become standard was the one by the Sanskrit paṇḍita Somanātha and the Tibetan translator ‘Bro Shes rab grags. This translation was at some point revised by Shong ston Rdo rje rgyal mtshan, and it is only this revised version that we have. This revised Shong version was again revised when the Jonang teacher Dolpopa asked Blo gros rgyal mtshan and Blo gros dpal bzang po to do so. Shong ston says in his colophon that he used two Sanskrit manuscripts when making his revision, and the two Jonang translators say in their colophon that they used many (mang po) Sanskrit manuscripts when making their revison. So the Jonang revised translation of the Kālacakra-tantra is a revision of the Shong ston revision of the translation by Somanātha and ‘Bro lo tsā ba (Dro lotsawa).

The Kālacakra-tantra is a text of unusual difficulty, not only because of its arcane subject matter, but especially because it is written entirely in the sragdharā meter. In this long meter every syllable is regulated as to its length, long or short. So the writer cannot just say things as he would in prose, but must make every syllable fit the meter. The Tibetan translation, too, is regulated by meter, in this case by the total number of syllables allowed per line. This means that syllables giving important grammatical information often had to be omitted to fit the meter. Somanātha and ‘Bro lo tsā ba when making their translation had to fit the meaning into the required number of Tibetan syllables. Likewise, when Shong ston and the two Jonang translators were making their revisions, they could not just say what they thought was meant, but rather had to somehow fit this into the meter.

As already said, the unrevised translation of the Kālacakra-tantra by Somanātha and ‘Bro lo tsā ba is no longer available. The revision of it by Shong ston is found in several editions or recensions of the Kangyur, including the Lithang, Narthang, Der-ge, Co-ne, Urga, and Lhasa blockprint recensions, and also in a blockprint with annotations by Bu ston. The Jonang revision of the Shong revision is found in the Yunglo and Peking blockprint recensions of the Kangyur, and also in a modern typeset edition with annotations by Phyogs las rnam rgyal. All of the editions or recensions have a number of typographical errors. This must be carefully taken into account when trying to ascertain the differences between the Shong version and the Jonang version. Sometimes even the differences between two or more recensions of the same version, such as the Narthang and Der-ge recensions of the Shong version, are such that the correct reading can only be ascertained by comparision with the original Sanskrit. Once the texts are established, it is only by comparison with the original Sanskrit that we can try to determine what the Jonang revisers were attempting to clarify or correct.

Here follows the edited and corrected Sanskrit text, an English translation (by myself), the edited and corrected Tibetan text as revised by Shong ston, and the edited and corrected Tibetan text as revised by the two Jonang translators. The differences between the Shong and Jonang versions are underlined. Some comments on these are then given. For access to the eight blockprint recensions mentioned above, I have used the comparative Bka’ ‘gyur published in China, vol. 77 (2008). Six of these give the Shong version and two of these give the Jonang version. Since two textual witnesses for the Jonang version are not sufficient, I have used the edition with annotations by Phyogs las rnam rgyal published in the Jonang Publication Series, vol. 17 (2008), and the manuscript with annotations by Phyogs las rnam rgyal reproduced in Dus ‘khor ‘grel mchan phyogs bsgrigs, vol. 4 (2007). This same manuscript was also reproduced in Dus ‘khor phyogs bsgrigs chen mo, vol. 25 (2014).

sarva-jñaṃ jñāna-kāyaṃ dina-kara-vapuṣaṃ padma-patrâyatâkṣaṃ

buddhaṃ siṃhâsana-sthaṃ sura-vara-namitaṃ mastakena praṇamya |

pṛcched rājā sucandraḥ kara-kamala-puṭaṃ sthāpayitvôttamâṅge

yogaṃ śrī-kālacakre kali-yug-a-samaye mukti-hetor narāṇām || 1 ||

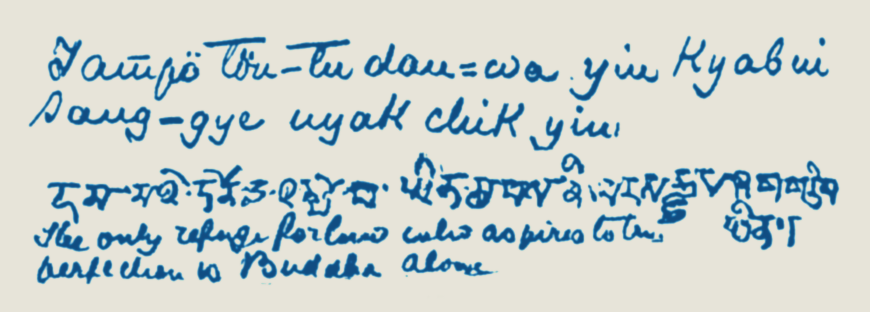

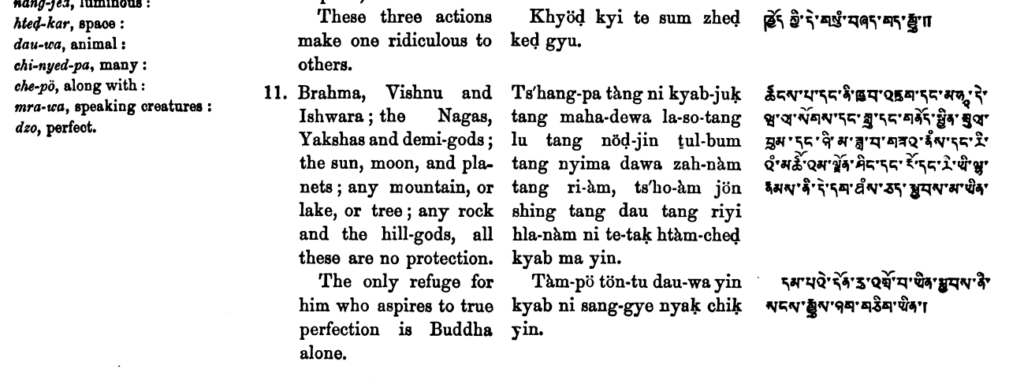

Having bowed with his head to the omniscient Buddha, who is the primordial wisdom body, which is the body of the sun, whose eyes are long like lotus petals, who is seated on a lion throne, who is bowed to by the best of gods, King Suchandra, having placed his joined lotus-hands on his head, asked for the yoga in the glorious Kālachakra, which latter is the group of vowels together with the consonants, for the sake of the liberation of human beings.

thams cad mkhyen pa ye shes sku dang nyin mor byed pa’i sku ste padma’i ‘dab ma rgyas pa’i spyan | |

sangs rgyas seng ge’i khri la bzhugs pa lha mchog rnams kyis btud la rgyal po zla ba bzang po yis | |

mgo bos rab tu phyag ‘tshal lag pa’i padma sbyar ba yan lag mchog la bzhag nas zhus pa ni | |

rnal ‘byor dpal ldan dus ‘khor ka phreng ldan pa’i a ‘dus la ste mi rnams dgrol ba’i don du’o | 1 | Shong

thams cad mkhyen pa ye shes sku dang nyin mor byed pa’i sku ste pad ma’i ‘dab ma rgyas pa’i spyan | |

sangs rgyas seng ge’i khri la bzhugs lha’i mchog rnams kyis ni btud la rgyal po zla ba bzang po yis | |

mgo bos rab tu phyag ‘tshal lag pa’i pad ma sbyar ba yan lag mchog la bzhag nas zhus pa ni | |

rnal ‘byor dpal ldan dus ‘khor ka phreng ldan pa’i a ‘dus su ste mi rnams dgrol ba’i don du’o | 1 | Jonang

Here the Jonang revisers have omitted the “pa” in “bzhugs pa,” “seated,” in order to make room for a newly added syllable, “ni” after “kyis.” The final “pa” in Tibetan words is often omitted in verse, and this does not usually create misunderstanding. The syllable “ni” typically marks where the subject is set off from the predicate. Here it sets off the subject, “by the best of gods,” “lha’i mchog rnams kyis,” from the predicate, “is bowed to,” “btud,” in this short subordinate clause. This short phrase is in the passive construction, which is the norm in Tibetan, and is also common in Sanskrit. In English, we would not regard “by the best of gods” as the subject, but in Sanskrit it is so regarded in passive phrases, and also in Tibetan. This whole phrase, “is bowed to by the best of gods,” is only a part of the longer description of what King Suchandra has bowed to, which takes up most of the first two lines of this verse. Hence it is one of the objects of the verbal, “having bowed to,” Sanskrit “praṇamya,” Tibetan “rab tu phyag ‘tshal.” In the Sanskrit, all of these objects of this verbal are individually declined in the accusative case. In the Tibetan, it is only the “la” after “btud” that shows the accusative for the several preceding objects of this verbal. This is common in Tibetan translations of Sanskrit verse, where economy as to the total number of syllables must be achieved. By adding “ni” before “btud,” perhaps the Jonang revisers wished to help avoid possible confusion regarding the larger function of the “la” after “btud.” They also changed “lha” to “lha’i,” adding the genitive “’i.” This spelled out the “of” in the “best of gods,” which otherwise was only implied, and it did so without adding a syllable.

Then in the last line the Jonang revisers changed “la” to “su” after “’dus,” “group.” This may be regarded as a formal correction. Of the seven “la don” particles, namely, “su, ru, ra, du, na, la, tu,” all having the same function of showing the accusative, dative, or locative case, “su” is supposed to be used after final “s.” But, of course, the rules are not always followed. The Sanskrit “samaye” shows that the locative case is intended here.

śūnyaṃ jñānaṃ ca binduṃ vara-kuliśa-dharaṃ buddha-devâsurāṃś ca

bāhye dehe pare ca prakṛtiṣu puruṣaṃ pañca-viṃśâtmakaṃ ca |

dehe viśvasya mānaṃ tri-bhuvana-racanāṃ bhukti devâsurāṇām

etad vyākhyāhi samyak tri-daśa-nara-guro maṇḍalaṃ câbhiṣekam || 2 ||

The empty, primordial wisdom, the drop, the best and the holder of the thunderbolt, buddhas, gods, and demons, in the outer, in the body, and in the other, spirit among the substances consisting of the twenty-fifth, the measure of the cosmos in the body, the arrangement of the three worlds, the enjoyment of the gods and of the demons, the maṇḍala, and the initiation; O teacher of gods and men, please explain this completely.

stong pa ye shes kyang ste thig le mchog mchog rdo rje ‘dzin pa sangs rgyas lha dang lha min yang | |

phyi dang lus dang gzhan la yang ste rang bzhin rnams la skyes bu nyi shu lnga pa’i bdag nyid dang | |

lus la sna tshogs tshad dang srid pa gsum gyi bkod pa lha dang lha min rnams kyi longs spyod dang | |

dkyil ‘khor dang ni dbang ste skabs gsum pa dang mi yi bla mas ‘di dag yang dag bshad du gsol | 2 | Shong

stong pa ye shes kyang ste thig le mchog dang rdo rje ‘dzin pa sangs rgyas lha dang lha min yang | |

phyi dang lus dang gzhan la yang ste rang bzhin rnams dang skyes bu nyi shu lnga pa’i bdag nyid dang | |

lus la sna tshogs tshad dang srid pa gsum gyi bkod pa lha dang lha min rnams kyi longs spyod dang | |

dkyil ‘khor dang ni dbang ste skabs gsum pa dang mi yi bla ma ‘di rnams yang dag bshad du gsol | 2 | Jonang

In the Shong version of this verse we have the phrase “mchog mchog rdo rje ‘dzin pa,” corresponding to the Sanskrit “vara-kuliśa-dharaṃ.” The Tibetan word “mchog” translates the Sanskrit word “vara,” meaning “best.” As may be seen, there is only one “vara” in the Sanskrit, while there are two “mchog”s in the Tibetan. This is because the Vimalaprabhā commentary explains this compound as an “eka-dvandva” (Jagannatha Upadhyaya Sanskrit edition, p. 48). More fully, this is an “eka-śeṣa,” “the remainder of one,” “-dvandva,” “dual.” This is a rare type of dual compound in which one of the members is not stated, but only implied, and only the other one remains. An example of this is “vṛkṣau,” the word “vṛkṣa,” “tree,” declined in the dual, meaning “vṛkṣa and vṛkṣa,” “tree and tree.” The Vimalaprabhā construes this compound as “varaś ca varaś ca kuliśa-dharaś ca vara-kuliśa-dharam,” meaning “best and best and holder of the thunderbolt.” This is how the translation “mchog mchog rdo rje ‘dzin pa,” in the Shong version was intended to be understood, as if the three terms were joined by “dang,” “and,” in between them. However, the additional “vara” is not found in the verse itself. So in keeping with the strict literal accuracy that characterizes the Tibetan translations of Sanskrit texts, the Jonang revisers removed the second “mchog” that was only implied, and replaced it with “dang,” showing that this phrase is to be understood as a dual compound, “the best and the holder of the thunderbolt.”

In the second line of this verse, the syllable “la” after “rang bzhin rnams” in the Shong version was replaced by “dang” in the Jonang version. The “la” intended the locative case, as seen in the Sanskrit “prakṛtiṣu,” “among the substances.” The “dang,” “and,” was presumably intended to show that “puruṣa,” “spirit,” is not among the twenty-four substances posited in the Sāṃkhya system. Rather, as the twenty-fifth principle, it forms a category of its own outside the substances. So unlike in the first line, where the Jonang version became a more literal translation, here in the second line it became a less literal translation.

In the last line, the last three syllables of the phrase “skabs gsum pa dang mi yi bla mas ‘di dag” in the Shong version have been changed to “ma ‘di rnams” in the Jonang version. The first of these three syllables in the Shong version, “mas,” has the instrumental ending “s,” “by,” yielding “by the teacher of gods and men.” Since Tibetan sentences are usually passive, the instrumental ending usually marks the subject. Something is done “by” the subject. This is with verbs other than imperatives, as we have here, Sanskrit “vyākhyāhi,” Tibetan “yang dag bshad du gsol,” “please explain.” With an imperative verb, when not the implied “you,” the subject would normally be in the vocative case, “O teacher of gods and men,” and would not have the intrumental ending. The change from “mas” to “ma” in the Jonang version has deleted the instrumental ending, allowing this to be understood as a vocative.

Interestingly, the corresponding Sanskrit phrase as found in all three printed editions, “tri-daśa-nara-guror,” is not in the vocative case. It is in the ablative or genitive case. Here, followed by “maṇḍalaṃ,” the natural reading would be “the maṇḍala of the teacher of gods and men.” The early Tibetan translations clearly did not read it this way. This discrepancy must be explained. The obvious answer is that the Sanskrit manuscripts that they translated from must have had the vocative, “guro,” rather than the ablative/genitive, “guror.” The difference is only a single letter, and in this combination it is merely a mark above the following Sanskrit letter. But the evidence of the printed Sanskrit editions is weighty, since in their aggregate they used several old palm-leaf manuscripts, and no variant reading is reported for this. This phrase is repeated verbatim in the Vimalaprabhā commentary, bringing in additional manuscript evidence. Again, no variant reading is reported here (Upadhyaya edition, p. 51). So which reading is correct? Fortunately, we now have access to at least three old Sanskrit manuscripts that were used in Tibet, and these can be checked. In 1971 Lokesh Chandra published a facsimile of a Kālacakra-tantra manuscript from Narthang monastery in Sanskrit Manuscripts from Tibet. Here the letters are slightly indistinct, but it appears to read “guror.” Another old palm-leaf manuscript that formed the primary basis for the edition of the Kālacakra-tantra by Raghu Vira and Lokesh Chandra (1966) and also the edition by Biswanath Banerjee (1985) has now become available online. It is from Nepal, and is now in the Cambridge University Library. As may be seen, https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01364/4, it clearly reads “guror.” Two other palm-leaf manuscripts used by Banerjee, which were photographed in Tibet, are not accessible to me to verify that they in fact read “guror” as in his edition. The printed edition of the Kālacakra-tantra that is included in the printed edition of the Vimalaprabhā was largely based, in volume 1 edited by Jagannatha Upadhyaya (1986), on a later but carefully written paper manuscript. I was able to check this manuscript from a microfiche of it made by the Institute for Advanced Studies of World Religions (MBB I-24). Contrary to the printed edition, it reads “guro” in both the Kālacakra-tantra verse (folio 29B, line 9) and also in the Vimalaprabhā commentary (folio 32B, line 11). An old palm-leaf manuscript of the Vimalaprabhā that was used in Tibet is held in the library of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta (G 10766). It reads “guro,” as I was able to see from a microfilm of it (folio 20B, line 7). Another such Vimalaprabhā manuscript was reproduced by Lokesh Chandra in 2010 in Sanskrit Manuscripts from Tibet. It clearly reads “guro” (folio 23B, p. 20, the fourth folio side on that page, line 4). I then checked my microfilm of another palm-leaf manuscript of the Vimalaprabhā that was not used in the printed edition, from the Asiatic Society of Bengal (G 4727). It, too, reads “guro” (folio 37A, line 5). So despite every printed edition reading the ablative/genitive “guror” with no variant reading reported, and although “guror” appears even in some early Sanskrit manuscripts, the correct reading is clearly the vocative “guro.” This agrees with the early Tibetan translations, and is what would be expected with an imperative verb as we have here.

The last of the three-syllable phrase in the Shong version, “dag” after “’di,” “this,” was changed to “rnams” in the Jonang version. Since both of these show the plural, turning “this” into “these,” this can be regarded as a formal change. However, “rnams” is unambiguously a plural marker, while “dag” can specifically translate the Sanskrit dual number. Since this line of the Tibetan translation begins with two items, the maṇḍala and the initiation, “’di dag” could be understood to only refer to these two, while “’di rnams” clearly refers to all the preceding.

tuṣṭo ‘haṃ te sucandra pravara-sura-narai rākṣasair daitya-nāgair

na jñātaṃ vīta-rāgaiḥ parama-muni-kulair yat tvayā pṛṣṭam etat |

nirvāṇâdyaṃ dharântaṃ pada-gati-sahitaṃ deha-madhye samastaṃ

yogaṃ vyākhyāyamānaṃ śṛṇu su-nara-pate maṇḍalaṃ câbhiṣekam || 3 ||

I am pleased with you, Suchandra. By the best gods and men, by rākshasas, daityas, and nāgas, by those whose passions are gone, by the lineages of the highest sages, this that was asked by you is not known. The entire yoga, beginning with nirvāṇa and ending with the earth, together with the paths of words [i.e., the classes of letters], inside the body, and the maṇḍala and the initiation are about to be explained. Listen, good king!

zla ba bzang po khyod la bdag mgu gang zhig khyod kyis dris pa ‘di ni rab mchog lha rnams dang | |

mi dang srin po lha min klu dang chags bral thub mchog rigs rnams dag gis shes pa min pas so | |

mya ngan ‘das pa la sogs ‘dzin ma’i mthar thug tshig gi bgrod pa dang bcas sbyor ba mtha’ dag ni | |

lus dbus su ste dkyil ‘khor dag dang dbang ni bshad par bya yis mi yi bdag po bzang po nyon | 3 | Shong and Jonang

The Jonang version of this verse is the same as the Shong version.

So far, we have not seen any doctrinal changes in the Jonang version, but only clarifications of the meaning, primarily by means of the grammar.

Notes on the English Translation and the Sanskrit Text:

verse 1:

“sun,” dina-kara, literally, “day-maker.”

“whose eyes are long like lotus petals,” padma-patrâyatâkṣaṃ. This is a bahuvrīhi or possessive compound, “he whose eyes are long like lotus petals.” Long or large eyes are a mark of beauty in India. The Vimalaprabhā in explaining this compound uses “dīrgha,” meaning “long,” a synonym of “āyata” in this compound.

“on his head,” uttamâṅge, literally, “on [his] highest limb.”

“the group of vowels together with the consonants,” kali-yug-a-samaye. The natural reading would be kali-yuga-samaye, “at the time of the age of strife.” The Vimalaprabhā commentary, however, does not even notice such a reading, giving instead the interpretation as translated. Note that the word “samaya” in the meaning “group,” Tibetan “’dus,” is found only in Buddhist Sanskrit and in Pali, not in classical Sanskrit.

verse 2:

“enjoyment of the gods and of the demons,” bhukti devâsurāṇām. The word “bhukti” cannot really stand alone like this, without being declined. Nor can it really form part of a compound with the following “devâsurāṇām.” It stands in this way because of the meter, which requires a short syllable here. The editor of this volume of the Vimalaprabhā, Jagannatha Upadhyaya, has put “bhukti(r)devâsurāṇām” to call attention to this problem, adding the declensional ending “r” in parentheses. Of course, it cannot actually be added, because it would make the syllable long.

“gods,” tri-daśa (in the phrase, “O teacher of gods and men,” tri-daśa-nara-guro), literally, “the thirty.” This is a common short form of “the thirty-three,” which a standard term for the thirty-three main gods in Hinduism.

verse 3:

“together with the paths of words,” pada-gati-sahitaṃ, explained in the Vimalaprabhā commentary as the classes of letters, i.e., the groups of gutturals, palatals, labials, etc. This is a good example of how words must be used unusually in order to fit the meter, especially here in the seven-syllable middle segment of a twenty-one syllable line, where the syllables must be six short followed by one long.

“about to be explained,” vyākhyāyamānaṃ. This is a present passive participle, meaning “being explained,” not “about to be explained.” It so happens that this present passive participle exactly fits the meter, so it was apparently used in place of the future passive participle. Since the Buddha has not yet begun his explanations, and therefore these things are not yet “being explained,” the intended meaning would be that of the future passive participle, “about to be explained.” None of the three possible forms of the future passive participle, neither the usual one, vyākhyātavyam, nor the other two possibilities, vyākhyeyam or vyākhyānīyam, would fit the meter.

“good king,” su-nara-pate, “king” is literally “ruler of men.”

Category: Jonangpa, Kalacakra, Kālacakratantra, Vimalaprabha |