Introduction

Several of the concepts central to the philosophy of H.P. Blavatsky’s (HPB’s) work The Secret Doctrine, may be defined in terms of “svabhâvât”. Some of these concepts will be listed in this introduction. In the following paragraphs we can have a look at some examples of the use of the term svabhâvât (svabhāva), in relevant scholarly, philosophical and religious works, to see if we can find any resemblance to the concept of svabhāva as it is presented in The Secret Doctrine.

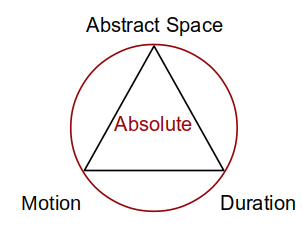

In the Proem to The Secret Doctrine (SD I, 1), in the “archaïc manuscript”, boundless abstract space is symbolised as an immaculate white disk on a dull background. In SD I, 35, abstract space is described as unconditional, and eternal (timeless or independent of time):

“What is that which was, is, and will be, whether there is a Universe or not; whether there be gods or none?” asks the esoteric Senzar Catechism. And the answer made is — SPACE.

In the very first śloka from the Book of Dzyan as presented in The Secret Doctrine, stanza 1 śloka 1 (SD I, 35), abstract space is called the eternal parent:

1. “THE ETERNAL PARENT (Space), WRAPPED IN HER EVER INVISIBLE ROBES, HAD SLUMBERED ONCE AGAIN FOR SEVEN ETERNITIES (a).”

The invisible robes in which the parent is “wrapped” are interpreted in stanza 1 śloka 5 as mūlaprakṛti, the one primordial substance. In stanza 1 śloka 5 (SD I, 40-41) then, abstract space is called darkness:

1.5 DARKNESS ALONE FILLED THE BOUNDLESS ALL (a), FOR FATHER, MOTHER AND SON WERE ONCE MORE ONE, […]

HPB explains in SD I, 41:

When the whole universe was plunged into sleep — had returned to its one primordial element — there was neither centre of luminosity, nor eye to perceive light, and darkness necessarily filled the boundless all.

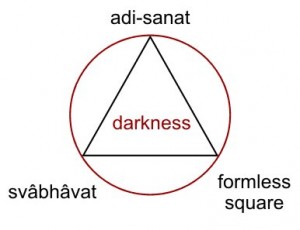

In stanza 2 śloka 5 (SD I, 60), we find the same identification, and furthermore, darkness is called father-mother, and svabhâvât:

2.5 […] DARKNESS ALONE WAS FATHER-MOTHER, SVABHAVAT, […]

This applies only to the state of pralaya, the sleep of the universe, and svabhâvât may appear in at least two respective stages. The nivṛitti (also incorrectly spelled nirvṛtti) stage is also called pradhāna, when svabhâvât is in darkness, while the pravṛtti stage is called prakṛti, when svabhâvât has become the manifested matter which is at the basis of the various planes of manifestation. Not in each case in HPB’s writings the term pradhāna is used for the unmanifested root of matter, but in volumes I and II of the SD we find it used consistently in this manner. For example in SD I, 257 we find:

the former term (pradhāna) being certainly synonymous with Mulaprakriti and Akasa, […]

Here we see that ākāśa is also identified with mūlaprakṛti, the unmanifested “root of matter”.

1. The Orthography of Svabhâvât

Concerning svabhâvât, Friedrich Max Müller reported the following in 1876 in his Chips from a German Workshop Vol. I. p 278:

The Svâbhâvikas maintain that nothing exists but nature, or rather substance, and that this substance exists by itself (“svabhâvât), without a Creator or a Ruler. It exists, however, under two forms : in the state of Pravritti, as active, or in the state of Nirvritti, as passive.

Daniel Caldwell has suggested that this passage might have been HPB’s source for the term svabhâvât, and that the ending in -ât would indicate the ablative case of svabhāva, meaning “by itself”. If this is true, these two terms would be two forms of the same base word, which is spelled in the current IAST orthography as svabhāva.

2. Svabhāva: Nature or Substance

Based on this identification of svabhâvât as svabhāva, we can look up this term in common dictionaries and start reviewing what was written in the time of HPB in sources she has consulted or might have consulted, which is not always clear. In this last quotation from Müller, he distinguishes two senses of the word svabhāva: “nature” and “substance”. Perhaps he is echoing Brian Houghton Hodgson at this point. In the standard Monier-Williams’ A Sanskrit-English Dictionary (MW), this second sense is not mentioned in the main lemmata for svabhāva and svabhāvāt:

m. own condition or state of being, natural state or constitution, innate or inherent disposition, nature, impulse, spontaneity

m. (…vāt or …vena or …va-tas or ibc.), (from natural disposition, by nature, naturally, by one’s self, spontaneously) ŚvetUp. Mn. MBh. &c.

A specific use of svabhāva or svabhāvāt as a philosophical term in Mahāyāna Buddhist literature as mentioned by HPB is not included in MW. In HPB’s time there were also the dictionaries by Horace Hayman Wilson (whom she held in high regard as a researcher), and later the great Sanskrit-German dictionary by Rudolf Roth and Otto von Böhtlingk, which also do not mention svabhāva as “substance”.

If we look at the Śvetāśvatara Upanishad (ŚvUp, ca. 400 BCE ±100), the oldest extant work where the term svabhāva is mentioned, in ŚvUp 1.2 we find in the discussion on the first cause of things, svabhāva as a possible first cause (tr. Robert Ernest Hume, 1921) :

kālaḥ svabhāvo niyatir yadṛcchā bhūtāni yoniḥ puruṣeti cintyam /

saṃyoga eṣāṃ na tv ātmabhāvād ātmā hy anīśaḥ sukhaduḥkhahetoḥ //

Time (kāla), or inherent nature (sva-bhāva), or necessity (niyati) or chance (yadṛcchā), or the elements (bhūta), or a [female] womb (yoni), or a [male] person (puruṣa) are to be considered [as the cause]; […]

This verse answers the question “kutaḥ sma jātā”, “whence are we born?”, from the previous verse. Again we find svabhāva as “inherent nature” and not as “substance”. Moreover, from the translation it is not clear if svabhāva is intended here as 1. inherent nature of individual entitites (pluralistic) or 2. of entities in general or the universe as a whole. (monistic) In the Book of Dzyan, svabhāva is in principle a monistic concept, as we have seen in the introduction to this article.

3. HPB’s quote from the Anugītā

In the SD, HPB refers to one extant work from the context of Hinduism where svabhāva is used in the sense of “substance”. In SD I, 571 she quotes the Anugītā:

“[…] Gods, Men, Gandharvas, Pisâchas, Asuras, Râkshasas, all have been created by Svabhâva (Prakriti, or plastic nature), not by actions, nor by a cause” — i.e., not by any physical cause.

In the 1882 translation of the Anugītā by K.T. Telang, a work HPB has consulted on other occasions, on p. 387 we find what is presumably the source of this quotation:

Gods, men, Gandharvas, Pisâkas, Asuras, Râkshasas, all have been created by nature5, not by actions, nor by a cause.

where note 5 refers to:

5. The original is svabhâva, which Arguna Misra renders by Prakriti.

From her substitution of “nature” by “Svabhâva (Prakriti, or plastic nature)” we may derive that HPB interprets svabhâva here as the term svabhâvât appearing in the Book of Dzyan, which is described as “plastic essence” (SD I, 61), the plastic root of physical Nature (SD I, 98), which in its “active condition” is called prakṛti.

Note 5 refers to the commentary to the Mahābhārata by Arjuna Miśra (16th c.), who, according to the note, renders svabhāva as prakṛti. We can read the original verse in book 14, chapter 50 (Bombay ed. 51), verse 11 of the Mahābhārata, the Anugītā being part of its Aśvamedha parvan:

devā manuṣyā gandharvāḥ piśācāsurarākṣasāḥ

sarve svabhāvataḥ sṛṣṭā na kriyābhyo na kāraṇāt || 14.50.11 ||

Indeed in this verse, “by nature” seems to be an inadequate translation for svabhāva. Although Arjuna Miśra, and HPB, have thought that in this verse svabhāva should be identified with prakṛti, it is still possible that the author has intended “inherent nature” and not “substance”. Just as in the quotation from the ŚvUp, it is not exactly clear here if svabhāva is intended as an individual (pluralistic) or a collective “cause”.

4. The Mahāvyutpatti

In the Mahāvyutpatti (Mv, Toh. 4346), the famous Tibetan-Sanskrit dictionary, a work from a Buddhist context dating back to the first half of the 9th century, the Sanskrit entry for prakṛti (no. 7497) is linked to Tibetan “rang bzhin”, “rang bzhin ngo bo nyid”, and “rang bzhin ngo bo nyid dam rang bzhin.” These three terms are expressions for svabhāva as the “inherent nature” of Mahāyāna Buddhism. The two terms rang bzhin and ngo bo nyid are derived from rang (own, self) and ngo or ngo bo (face), and therefore their primary meaning will be closer to svabhāva as “nature” than to “substance”. The next entry in the Mv, no. 7498, is indeed svabhāva, to which are linked the same three expressions.

| No. | Sanskrit | Tibetan |

| 7497 | prakṛti | rang bzhin; rang bzhin ngo bo nyid; rang bzhin ngo bo nyid dam rang bzhin |

| 7498 | svabhāva | rang bzhin; rang bzhin ngo bo nyid; rang bzhin ngo bo nyid dam rang bzhin |

This may suggest that at the time the Mv was composed, the terms svabhāva and prakṛti were seen as completely synonymous, by the team of creators of the dictionary, but also by extension by the lotsavas who considered the Mv their golden standard. However, it does not say anything about whether in the Mv svabhāva/prakṛti is considered a pluralistic or monistic concept or perhaps even both.

5. The Svabhāva Mantra

Eugène Burnouf, on p. 393 of his Introduction à l’Histoire du Bouddhisme Indien (1876), notices that “the word Nature does not render at all that which the Buddhists understand as Svabhāva” [tr. IdB]:

They see it at the same time as Nature which exists in itself, absolute Nature, the cause of the world, and as the own Nature of every existence, that which constitutes that it exists.

Here we have the two standpoints, of Mahāyānist monism and Hīnayāna pluralism, combined into one. In connection with the elusive or illusive school of the Svābhāvikas (spelled by Burnouf with the extra macron), Burnouf remarks on p. 395: “When they were asked: Where do existences come from? they answered: Svabhāvāt, ‘from their own nature’ — And where do they go after this life? — Into other forms produced by the irresistable influence of that same nature. […]”.

On pp. 572-3 Burnouf adds:

The second of the two meanings of the word Svabhāva, which I set out in my text, is perfectly demonstrated in a passage of the Pañcakramaṭippaṇī which I think is useful to cite. The yogi must, according to the text of that work, pronounce the following axiom: Svabhāva śuddhaḥ sarvadharmāḥ svabhāva śuddho ‘ham iti. ‘All conditions or all existences are produced from their own nature; I am myself produced from my own nature.’ I believe that this meaning of svabhāva is the most ancient; if, as Hodgson thought, the Buddhists understood by this term the abstract nature, this metaphysical notion may have been added to the word afterwards, of which the natural interpretation is that which is indicated by the axiom I have just cited. It may be useful to remark that taking the participle śuddha, in the sense of ‘complete, accomplished;’ is colloquial in Buddhist Sanskrit.

The ṭippaṇī in question is also known as the Piṇḍīkramaṭippaṇī, which is Parahitarakṣita’s short commentary on the first part of the tantric Nāgārjuna’s Pañcakrama. Both the Pañcakrama and the ṭippaṇī were published by Louis de la Vallée Poussin in 1896, in one volume in the series Études et textes tantriques of Ghent university. On p. 15, lines 5-7 we find this passage. (see the Sanskrit Texts division of the Book of Dzyan web site, at http://prajnaquest.fr/blog/sanskrit-texts-3/sanskrit-buddhist-texts/)

Burnouf’s “axiom” is widely known as a mantra, under various names. It is called Svabhāva Mantra, Śuddha Mantra, or Śūnyata Mantra although this name is also used for another well known mantra. It is part of the sādhanas of quite a number of different traditions. Since the Pañcakrama and Piṇḍīkramaṭippaṇī are (sub-) commentaries to the Guhyasamājatantra, we might expect to find this mantra in the Guhyasamāja root text, but, searching visually several times, I have not been able to find it there. It is however a part of a commonly used daily sādhana of Guhyasamāja. In the Sādhanamālā, which is a later collection of 312 Buddhist ceremonial practices, the mantra is found 30 times. An example of a ceremony is the sādhana of Tārā, which is also studied by Stephan Beyer in The Cult of Tara. The mantra is found there as part of the Four Mandala Offering to Tara, where it is used to purify the location and attributes for the ritual, before the ceremony. (p. 180)

The mantra is also part of long and short versions of the Kālacakra sādhana, and as such it is discussed by David Reigle in his article on Sanskrit Mantras in the Kālacakra Sādhana. It was published in As Long as Space Endures: Essays on the Kālacakra Tantra in Honor of H.H. the Dalai Lama, where the mantra is found on p. 302. As a source for this mantra, Reigle refers to the Kālacakrabhagavatsādhanavidhiḥ (Toh. 1358). His translation is the following:

Oṃ svabhāvaśuddhāḥ sarvadharmāḥ svabhāvaśuddho ‘ham.

oṃ; Naturally pure are all things; naturally pure am I.

In this translation, svabhāvaśuddhāḥ is interpreted as “pure of nature”, or “pure by nature” instead of Burnouf’s “produced from its/their own nature”.

Lama Thubten Yeshe, in An Explanation of the Shunyata Mantra and a Meditation on Emptiness (in: Mandala, January/March 2009) explains the meaning of this same mantra as follows:

Also, this mantra contains a profound explanation of the pure, fundamental nature of both human beings and all other existent phenomena. It means that everything is spontaneously pure – not relatively, of course, but in the absolute sense. From the absolute point of view, the fundamental quality of human beings and the nature of all things is purity.

Svabhāva is here interpreted by Lama Yeshe as the “fundamental nature” of entities, or absolute reality, called paramārtha or pariniṣpanna in the Book of Dzyan. Ultimate reality or absolute reality is “pure” in the sense that it is the state of matter (mūlaprakṛti/prakṛti) where it is still unmanifested, or as HPB might have called it, non-manvantaric, or nivṛtti.

In the three examples presented here svabhāva is viewed also as absolute reality, paramārtha in Madhyamaka terminology, and not only as conditional reality, saṃvṛtti. Of course in any form of Buddhism, “natural purity” would be associated with “non-ego”, but in a different sense, the term svabhāva is commonly found in Madhyamaka oriented Buddhist writings. For example in the term niḥsvabhāva, often used as a synonym for nairātmya, anātman or “non-ego”, it indicates exactly the opposite, that is svabhāva only as conditional reality, or in HPB’s corresponding terminology, pravṛtti as opposed to nivṛtti.

The Book of Dzyan on the other hand explicitly describes svabhāva as going through the two different stages: 1. nivṛitti, when “darkness alone was […] svabhâvât” (“in paramārtha”, absolute reality), and 2. pravṛtti, when svabhāva is prakṛti, the basic substance of the manifested universe, that is conditional reality.

6. Hodgson’s Essays

On p. 73 of Brian Houghton Hodgson’s Essays on the Languages, Literature and Religion of Nepal and Tibet (1874) we find a list of principles from the “Svabhavika doctrine”, the first of which appears to be a translation of the Svabhāva Mantra:

All things are governed or perfected by Swabháva; I too am governed by Swabháva.

This is again a very different translation, where śuddha is taken as “governed/perfected by”. David N. Gellner responds to this in his 1989 article Hodgson’s Blind Alley? On the So-Called Schools of Nepalese Buddhism, calling it a misunderstanding of the term svabhāvaśuddha, which he translates as “free of essence”.

The “Ashta Sáhasrika” is given by Hodgson as a reference, but I have not found the mantra literally in the text of the Aṣṭasāhasrikāprajñāpāramitā. Some similar passages are to be found in the text, of which the following is an example (Edward Conze’s translation p. 250 and Sanskrit from ed. Vaidya p. 211, my (IdB’s) comments in square brackets):

Subhuti: But if, O Lord, as we all know, all dharmas [Skt. sarvadharmāḥ] are by nature perfectly pure [Skt. prakṛtipariśuddhāḥ], […]

The Lord: So it is, Subhuti. For all dharmas [sarvadharmāḥ] are just by (their essential original) nature perfectly pure [Skt. prakṛtyaiva pariśuddhāḥ]. When a Bodhisattva who trains in perfect wisdom […] remains uncowed although all dharmas [Skt. sarvadharmeṣu] are by their nature perfectly pure [Skt. prakṛtipariśuddheṣu], then that is his perfection of wisdom [Skt. prajñāpāramitāyāṃ].

Here we see that instead of svabhāvaśuddha (Reigle: pure by nature) the compound prakṛtipariśuddha (Conze, 2nd ed. 1975: by nature perfectly pure) is used in the same sense, reflecting the semantic agreement between svabhāva and prakṛti.

Further, the Tibetan version in the Derge Kanjur (Toh. 12) shows how the compound was analysed by the lotsavas of the Aṣṭasāhasrikāprajñāpāramitā: it was taken as rang bzhin gyis yongs su dag pa, which is “completely pure by nature”, as opposed to “free of essence”.

7. Prasannapadā and Mūlamadhyamakakārikā

In Candrakīrti’s Prasannapadā (PsP), we find a lengthy discussion of the concept of svabhāva. In the 1931 partial edition of Stanisław Schayer, Ausgewählte Kapitel…, in an extensive note on pages 55-57, four different meanings of svabhāva are distinguished (paraphrased IdB):

- Svabhāva as “nījam ātmīyam svarūpam”, an “essential” as opposed to “accidental” quality, like the hotness of fire. This is an idea compatible with Hīnayāna pluralism.

- Svabhāva as svalakṣaṇa, the own individual mark which is carried by the individual substrate of a dharma. The Hīnayānists are called Svabhāvavādins in the sense that they accept a manyfold of these individual substances (pluralism).

- Svabhāva as equivalent of prakṛti, of upādāna [[material cause]] and of āśraya [[basis of perception]], of the unchanging, eternal substrate of all changes. In the Hīnayāna schools, the Vaibhāṣikas accept this view, while the Sautrāntikas agree with the Mādhyamikas at this point, calling a transcendental lakṣya [[characteristic]] completely illusory. [[But being Hīnayāna schools, both of these are considered pluralist.]]

- Svabhāvaḥ as “svato bhāvaḥ”, the absolute being, “nirapekṣaḥ svabhāvaḥ”. The universe as “one and whole” is absolute. This idea is not compatible with Hīnayānist pluralism.

In the third and fourth points we may recognise concepts similar, both in a different way, to the svabhāva presented in the Book of Dzyan. In the text of the PsP, chapter XV § 2 (Schayer § 5 p. 63, cp. Vaidya ed. p. 116) the third point is analysed as follows (tr. from German IdB):

yā sā dharmāṇāṃ dharmatā nāma, saiva tatsvarūpam | atha keyaṃ dharmāṇāṃ dharmatā? dharmāṇāṃ svabhāvaḥ | ko ‘yaṃ svabhāvaḥ? prakṛtiḥ | kā ceyaṃ prakṛtiḥ? yeyaṃ śūnyatā | keyaṃ śūnyatā? naiḥsvābhāvyam | kimidaṃ naiḥsvābhāvyam? tathatā | keyaṃ tathatā? tathābhāvo ‘vikāritvaṃ sadaiva sthāyitā | sarvathānutpāda eva

Diese Eigenwesen [[tatsvarūpam]] ist die dharmatā der dharmas. — Und was ist die dharmatā der dharmas? — Der svabhāva der dharmas. — Und was ist dieser svabhāva? — Die prakṛti. — Und was ist diese prakṛti? — Die śūnyatā. — Und was ist diese śūnyatā? — Das naiḥsvābhāvya. — Und was is dieses naiḥsvābhāvya? — Die tathatā, d.h. die Unwandelbarkeit der wahren Beschaffenheit (tathābhāvāvikāritva), das ewige Beharren [in seinem An-sich-Sein] (sadā sthāyitā), das absolute Nicht-entstehen (sarvadānutpāda).

This own essence [[tatsvarūpam]] is the “entitiness” of entities. And what is the “entitiness” of entities? It is the svabhāva of entities. And what is this svabhāva? It is its basic material. And what is this basic material? It is emptiness. And what is this emptiness? It is the fundamental absence of svabhāva. And what is this fundamental absence of svabhāva? It is thusness, that is the unique property of the true being-thus, the eternal fixedness [in its being per se], the absolute non-origination.

To Candrakriti this line of reasoning proves that svabhāva cannot exist as a basic substance in which (or on the basis of which) change is taking place. The reasoning is based on Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK) XV.8, to which this PsP passage is a commentary (tr. Mark Siderits and Shōryū Katsura, 2013):

yady astitvaṃ prakṛtyā syān na bhaved asya nāstitā |

prakṛter anyathābhāvo na hi jātūpapadyate ||

If something existed by essential nature (prakṛti), then there would not be the nonexistence of such a thing. For it never holds that there is the alteration of essential nature.

8. Conclusions

The examples discussed here, from the Anugītā, the Mahāvyutpatti, the Svabhāva Mantra and the Prasannapadā/Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, do not sufficiently show that the term svabhāva has been used, in original Hindu or Buddhist texts, not only in the sense of an “inherent nature”, but also in the sense of “substance”. In the Book of Dzyan it is described primarily as “substance”.

In Buddhism, pluralism is generally associated with Hīnayāna and monism with Mahāyāna. We have seen that in Buddhist texts another distinction of two senses of the word svabhāva may be recognised: in the svabhāva mantra we have found the term svabhāva as “fundamentally pure”, while the part svabhāva in the “doctrine of niḥsvabhāva” is used as exactly the opposite. We can define these two senses of the svabhāva as nivṛtti and pravṛtti respectively. In the Book of Dzyan, svabhāva is described primarily as “monistic”, but going through the nivṛtti and pravṛtti phases of manifestation. This may imply that svabhāva is in these two phases “monistic” and “pluralistic” respectively. •

Attachments

Category: Book of Dzyan, Cosmogenesis, Mulaprakriti, Space, Svabhavat | No comments yet