1. Introduction on Shenism

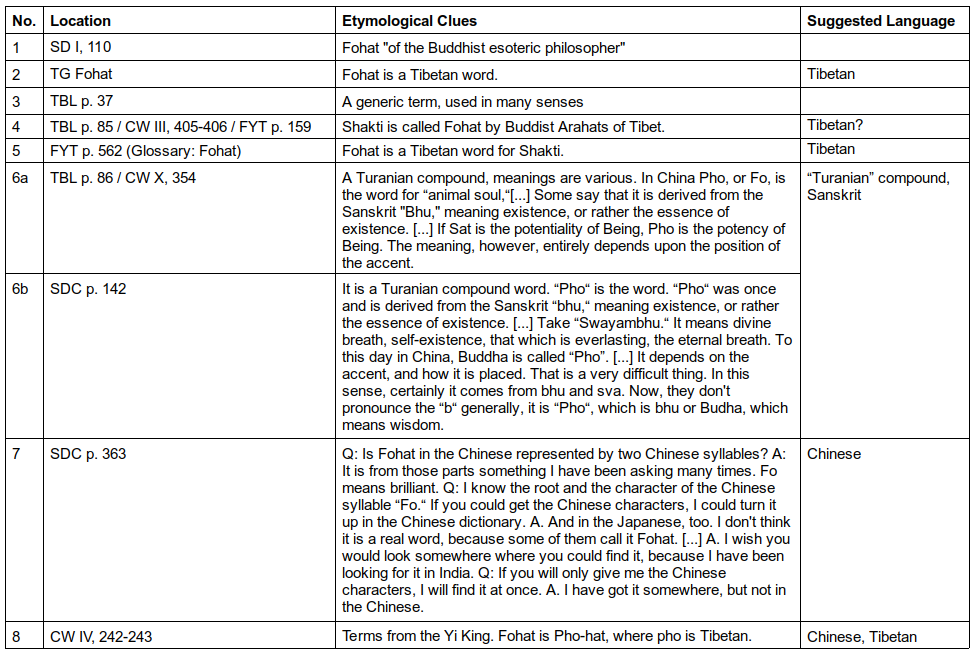

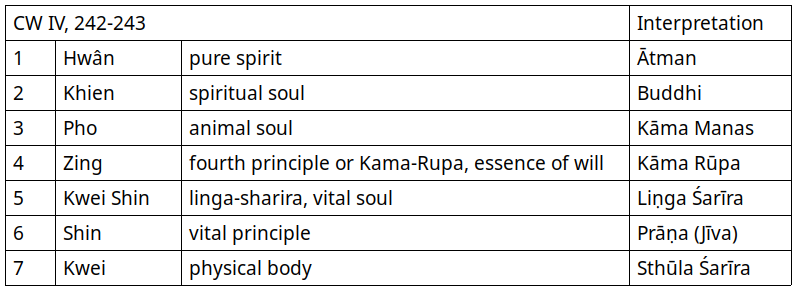

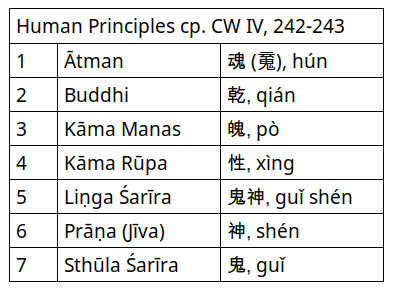

In a previous article, On the Etymology of the Term Fohat, I have identified with reasonable certainty the syllable “fo” in the term “fohat”. H.P. Blavatsky (HPB) mentions in an editorial note to an article in The Theosophist entitled Theosophy and the Avesta (see also CW IV, 242-243), a number of terms from Chinese traditional religion and their corresponding principles as part of the “septenary division of man”. In the same note she refers to the 1847 work A Dissertation on the Theology ofthe Chinese by Walter Henry Medhurst (1796-1857)1, where the Chinese syllable 魄 (pò) was found2, corresponding to the syllable “fo” of The Secret Doctrine (SD). Further research exposed quite a few interesting connections between the text of the stanzas of volume one of the SD, and elements of Chinese Traditional Religion and the literature connected with it, which I will describe in the following paragraphs of this article.

Chinese traditional religion or Chinese folk religion is usually defined as the syncretic forms of the three great religions of China, Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism, and the veneration of the shén and the ancestors. All of these components occur in Chinese traditional religion, mixed in different proportions, varying with time in different social settings. This multidimensional and dynamic religious complex was first called “shenism” by the anthropologist Allan J.A. Elliott in his 1955 work Chinese spirit-medium cults in Singapore.3

Traditional Chinese Medicine, acupuncture, several forms of divination and astrology, and also several forms of martial arts and their derivatives are connected to shenism, to various degrees. Japanese Shinto has strong parallels with shenism, and the syllable shin in the word shinto (神道, Chin. shén dào, the way of the shén) is cognate with shén (神). The shén (神) themselves are called kami (神, the same character) in Japanese. According to scholars in the field, the veneration of the shén is very ancient, however it would have evolved particularly strong during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). Today, shenism is still very popular in China and according to some researchers it is the most important religion in mainland China, with more than a quarter of the Chinese population being considered shenist. That would amount to more than 375 million people.4

2. The Divine Breath

Medhurst explores in his dissertation the meaning of the word shîn (神, pīnyīn: shén, spirit), summing up different occurrences of this word in Chinese dictionaries and classical works. To theosophists, the shén are most easily explained as the dhyan chohans in the SD. The same term dhyan chohans is used for the seven great lords of meditation as well as for the hierarchies of beings under their rule, while similarly the word shén is also used to denote both of these in the context of Chinese religion.

On p. 7 of his dissertation, Medhurst translates and paraphrases several definitions from the famous Kāng Xī dictionary (康熙, 1716 CE) appearing under shîn (神, shén, spirit), one of which explains the relations between shîn (shén), kweì (guǐ), hwăn (hún), pĭh (HPB’s Pho, 魄, pò), the life breath k’he (qí, 祇), and the fundamental concepts of 隂 (yīn) and 陽 (yáng)5:

In the next definition of 神 Shîn, given in the Dictionary, we meet with 鬼神 kweì shîn, under which the writer says, 陽魂爲神隂魄爲鬼 the soul of the male or superior principle of nature [陽, yáng] is called 神 shîn, and the anima of the female or inferior principle of nature [隂, yīn] is called 鬼 kweì; again, lest we should suppose that anything really divine is intended by the 魂 hwăn and 魄 pĭh, he says 氣之伸者爲神屈者爲鬼 the expanding quality of the breath or spirit of nature [祇, qí] is the 神 shîn, and its contracting quality the 鬼 kweì.

We could compare this text to śloka 10 and 11 of stanza III (SD I, 83):

10. FATHER-MOTHER SPIN A WEB WHOSE UPPER END IS FASTENED TO SPIRIT (Purusha), THE LIGHT OF THE ONE DARKNESS, AND THE LOWER ONE TO MATTER (Prakriti) ITS (the Spirit’s) SHADOWY END; AND THIS WEB IS THE UNIVERSE SPUN OUT OF THE TWO SUBSTANCES MADE IN ONE, WHICH IS SWABHAVAT (a).

11. IT (the Web) EXPANDS WHEN THE BREATH OF FIRE (the Father) IS UPON IT; IT CONTRACTS WHEN THE BREATH OF THE MOTHER (the root of Matter) TOUCHES IT. THEN THE SONS (the Elements with their respective Powers, or Intelligences) DISSOCIATE AND SCATTER, TO RETURN INTO THEIR MOTHER’S BOSOM AT THE END OF THE “GREAT DAY” AND REBECOME ONE WITH HER (a). WHEN IT (the Web) IS COOLING, IT BECOMES RADIANT, ITS SONS EXPAND AND CONTRACT THROUGH THEIR OWN SELVES AND HEARTS; THEY EMBRACE INFINITUDE. (b)

The “breath of fire” in this comparison corresponds to shîn and the “breath of the mother” correpsonds to kweì. The “fire”, or “father”, matches the “superior principle of nature” (yáng) and the mother the “inferior principle of nature” (yīn). Father-Mother is the unity of yīn and yáng. This is a thought that we might have had when we first read these ślokas, but here we have it layed out for us. Mencius calls the “breath or spirit of nature” qí, which is generally known from traditional Chinese medicine and other fields of interest, often spelled “chi” or “ki”. The soul of the male or superior principle of nature (yáng) is actually called hún in Medhurst’s text, and the anima of the female or inferior principle of nature (yīn) is called pò. The hún and pò are called shén and guǐ since their “qualities” of expanding and contracting are shén and guǐ respectively.

In śloka 11 the sons expand and contract, being under the influence of the qualities of the breath (qí). The sons are the (seven) elements, but they have (seven) corresponding powers or intelligences. Elsewhere in the SD, the sons are called the sons of fohat, who are also his brothers. Fohat is himself one of the sons (powers), or the “synthesis” of these powers. (SD I, 293) The sons expand and contract “through their own selves and hearts”, because they are forces which are intrinsically of expanding (shén) or contracting (guǐ) quality. As we know, in the summary to the first part of the first volume of the SD (I, 269-299), they are described as six primary forces, or śakti’s, and as the six hierarchies of dhyan chohans (dhyāni buddhas).

On p. 5 Medhurst continues to cite from the Kāng Xī dictionary:

[…] for 申卽引也 to expand […] means to lead forth; for 天主降氣以感萬物 heaven manages or directs the sending down of the k’he or breath of nature to influence all things, 故言引出萬物 therefore it is said, lead forth all things. […] It is Heaven that sends down its 氣 breath or spirit to influence or lead forth all things, and Shîn is the spirit thus employed.

We may compare these passages to śloka 12 (SD I, 85):

12. THEN SVABHAVAT SENDS FOHAT TO HARDEN THE ATOMS. EACH (of these) IS A PART OF THE WEB (Universe). REFLECTING THE “SELF-EXISTENT LORD” (Primeval Light) LIKE A MIRROR, EACH BECOMES IN TURN A WORLD.* . . .

On p. 15 in Medhurst’s dissertation we find also the element of the “web”, here a “net”, spun between heaven and earth, or spirit and matter in the Book of Dzyan:

Betwixt heaven and earth there is nothing so great as this 氣 breath of nature; that which enters into every fibre and atom is the male and female principle of nature, and that which incloses heaven and earth as in a net, is this male and female principle of nature.

This fragment is, according to Medhurst, a commentary to a quote from Confucius (孔子, Kǒng Zǐ, 551-479 BCE), but I have as yet not been able to find original texts of the quote or its commentary. I think however, that the correspondence with the already cited ślokas 10 and 11 is evident.

3. Father-Mother

In the Shū jīng (書經), the Book of Documents, originally written before or at the beginning of the Han dynasty, we find again the theme of heaven and earth as the basis of all subsequent phenomena. In Legge’s 1879 translation in volume 3 of the Sacred Books of the East series (p. 125), we find for example about the emperor:

Heaven and earth is the parent of all creatures; and of all creatures man is the most highly endowed. The sincerely intelligent (among men) becomes the great sovereign; and the great sovereign is the parent of the people.

In the first phrase of this quotation we read the word “parent”, a word we know is used in the first śloka of the Book of Dzyan as it is presented in the SD. Interestingly, in the English sentence by Legge, heaven and earth are plural, but are translated as singular. We have here an example of “heaven-earth”, a nominal compound in the Chinese source text, translated by Legge as a single noun. The word parent however, is also a nominal compound in the source text, namely 父母 (fù mǔ), which is litterally “father-mother”.

At the time HPB wrote the SD, there was at least one translation which rendered fù mǔ literally as father-mother. In the 1770 French translation by sinologists Joseph de Guignes and Antoine Gaubil (Le chou-king, un des livres sacrés des Chinois, p. 150), the same quotation from Confucius is as follows:

Le Ciel & la terre ſont le pere & le mere de toutes choſes. L’homme, entre toutes ces choſes, eſt le ſeul qui ait un raiſon capable de diſcerner; mais un Roi doit l’emporter par ſa droiture & pas ſon diſscernement; il eſt maître des hommes, il eſt leur pere & leur mere.

Heaven and earth are the father and mother of all things. Man, among all these things, is the only one who has a rationality capable of discerning; but a King must prevail by his righteousness and not his discernment; he is master of men, he is their father and their mother. [tr. IdB]

Much later, that is after the SD was written, sinologist William Edward Soothill actually uses the compound father-mother in his English translation (1913, The Three Religions of China, p.196):

Heaven and earth are the father-mother of all creatures, and of all creatures men are the most intelligent. The sincere, wise, and understanding among them becomes the great sovereign, and the great sovereign is the father-mother of the people.

Without unambiguously identifying the source of HPB’s use of father-mother in śloka 10 and 11 of stanza III and other places, we can imagine that this characteristic grammatical feature of the Book of Dzyan as given by HPB might be based upon the Chinese nominal compound.

4. Being is Non-Being

One of the ideas we come across in the Book of Dzyan is the “identity of opposites”, in particular when it comes to Being and Non-Being. HPB herself calls it a paradox or a “contradiction in terms”. We find it in several places in the first stanza, for example in SD I, 42:

6. […] THE UNIVERSE, […] TO BE OUTBREATHED BY THAT WHICH IS AND YET IS NOT. NAUGHT WAS.

We find HPB’s commentary on 6 in SD I, 43 under (c):

(c) By “that which is and yet is not” is meant the Great Breath itself, which we can only speak of as absolute existence, but cannot picture to our imagination as any form of existence that we can distinguish from Non-existence.

In SD I, 44 we find:

7. […] THE VISIBLE […] RESTED IN ETERNAL NON-BEING — THE ONE BEING.

The commentary on 7 we find in SD I, 45 under (b) (the page header of p. 45 is “BEING AND NON-BEING”):

(b) The idea of Eternal Non-Being, which is the One Being, will appear a paradox to anyone who does not remember that we limit our ideas of being to our present consciousness of existence; […] In our case the One Being is the noumenon of all the noumena which we know must underlie phenomena, and give them whatever shadow of reality they possess, but which we have not the senses or the intellect to cognize at present.

In SD I, 47 paramārthasatya (absolute truth) and saṃvṛttisatya (relative truth) are contrasted:

9. […] Absolute Being and Consciousness which are Absolute Non-Being and Unconsciousness […]

This idea of the “identity of opposites” is also found in Lao Tze’s well-known classic Tao Te Ching (道德经, dào dé jīng). In the Introductory to the SD (I, xxv), the “Tao-te-King” is mentioned, and its 1842 translation into French by Stanislas Julien. This translation was the first translation of the Tao Te Ching into a Western language, and an outstanding piece of scholarly work. The idea of identity of opposites is presented in chapters I and II of the Tao Te Ching: in chapter I the concept of Tao itself is explained, while in chapter II the unity of opposites is discussed. In chapter II we find in Julien’s text:

故有無相生。

C’est pourquoi l’être et le non-être naissent l’un de l’autre.

That is why being and non-being are born from each other. [tr. IdB]

An example of a more modern English translation of the same passage would be that of John C.H. Wu (1961):

Indeed, the hidden and the manifest give birth to each other.

The terms hidden and manifest may be closer to the SD, but they are not literal translations.

On p. 8 in Julien, in the comments of the later editors, we find in “edition B” from the Song era:

The non-being produces the being; the being produces the non-being. These beings, not being able to subsist eternally, end by returning to the non-being. [tr. IdB]

We can see here, that being and non-being are described as co-originated and interdependent. They create, complement and shape each other. We may associate this with yin and yang as complementary factors in the universe. The Book of Dzyan however goes one step further, in saying that they are identical, or that they are one and the same noumenon.

A different source of the SD on this topic is Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s Wissenschaft der Logik. In SD II, 449n we find:

* The Hegelian doctrine, which identifies Absolute Being or “Be-ness” with “non-Being,” and represents the Universe as an eternal becoming, is identical with the Vedanta philosophy.

and in SD I, 16 we find a similar sentence:

The ABSOLUTE; the Parabrahm of the Vedantins or the one Reality, SAT, which is, as Hegel says, both Absolute Being and Non-Being.

and in SD II, 490:

A thing can only exist through its opposite — Hegel teaches us […]

For comparison: in Hegel’s Wissenschaft der Logik we find for example in Vol. I p. 12:

Der Anfang enthält alſo beydes, Seyn und Nichts; iſt die Einheit von Seyn und Nichts; — oder iſt Nichtseyn, das zugleich Seyn, und Seyn, das zugleich Nichtseyn iſt.

The beginning therefore contains both, Being and Nothing; is the Unity of Being and Nothing; — or is Non-Being, which is at the same time Being, and Being, which is at the same time Non-Being. [tr. IdB]

and on Becoming out of Non-Being and Being, Vol. I. p. 23:

Ihre Wahrheit iſt also dieſe Bewegung des unmittelbaren Verſchwindens des einen in dem andern; das Werden;

Its truth is therefore this movement of the immediate disappearance of the one in the other; the becoming; [tr. IdB]

Here it is clear that there is an actual identity of opposites, which is perhaps a deeper level of insight which may be associated with the so-called yin and yang symbol. The black and white dots may be thought of as representing this idea. The movement suggested by the two halves may represent the eternal becoming, which is called Motion in the text of the SD, and is symbolised in the Book of Dzyan as the Great, or Divine, Breath.

5. The Great Extreme

Searching the SD for Chinese philosophy and related topics, we find Confucius and confucianism mentioned twenty-three times in volumes I and II. In these locations, we come across the “Great Extreme” several times. It is a term from neo-confucianism, but connected to the ancient philosophy of the I-Ching (易經, yì jīng), the Book of Changes. It signifies the “the commencement ‘of changes’ (transmigrations)”. (SD I, 440) Its character representation is 太極 (tài jí). Different Western scholars have used different translations of his term, ranging from “le grand faîte”, “magnus terminus”, “la grande limite” (Guillaume Pauthier), “le grand terme” (Joseph Prémare), “the Grand Terminus” (James Legge), to “the Great Extreme”, a term used by Medhurst in his already mentioned Dissertation.

HPB not only had read Medhurst’s Dissertation on this topic, but also Legge’s well-known translation of the I-Ching with its appendices. This translation was first published in 1882 as volume 16 in Max Müller’s Sacred Books of the East series. For instance, on p. 373 as part of Legge’s translation of the Xì Cí (繫辭) I.11, we find:

70. Therefore in (the system of) the Yî there is the Grand Terminus, which produced the two elementary Forms. Those two Forms produced the Four emblematic Symbols, which again produced the eight Trigrams.

This fragment is rendered in SD I, 440. The Yî (易, yì) is of course the I-Ching, and the two elementary forms are symbolised there by the straight and broken lines of the system of the I-Ching, which is its representation of the cosmos. With two basic lines, 26=64 hexagrams are formed, each one characterising a stage in a model process of evolution.

In a different appendix to the I-Ching, the Xù Guà (序卦), in paragraph 1 (tr. Legge, appendix VI, p. 433), we find:

When there were heaven and earth, then afterwards all things were produced. What fills up (the space) between heaven and earth are (those) all things. Hence (Qian [hexagram I, 天, qián, heaven] and Kun [hexagram II, 坤, kūn, earth]) are followed by Zhun [hexagram III, 屯, tún, sprouting].

So, from the Great Extreme, heaven and earth are produced, the “two elementary forms”, “the twofold” (兩儀, liǎng yí), which serves as a basis for all other productions.6

Just for comparison, we can read again part of stanza III śloka 10 (SD I, 83):

10. FATHER-MOTHER SPIN A WEB WHOSE UPPER END IS FASTENED TO SPIRIT (Purusha), THE LIGHT OF THE ONE DARKNESS, AND THE LOWER ONE TO MATTER (Prakriti) ITS (the Spirit’s) SHADOWY END;

In SD II, 553, the Great Extreme (太極, tài jí) is identified as the “concealed unity of the secret doctrine”, and compared to parabrahman, ein-sof and equivalent concepts from different cultural backgrounds. These are however limitless, noumenal instances, while the neo-confucian philosophers generally distinguish between the Great Extreme and different varieties of infinity. The term “extreme” itself signifies a limit, and the Great Extreme, or Terminus, is defined as an upper limit of the manifested cosmos. Zhū Xī (朱熹, 1130-1200), one of the most important thinkers among the “Sung sages”, places another concept next to the Great Extreme, namely 無極 (wú jí), literally “without boundary”. We can think of it as not only without spatial boundary, but also without temporal limitations. Zhū Xī inserts between these two characters the particle 而 (ér, and) to form a new concept, 無極而太極, wú jí ér tài jí, which is symbolised by a circle. The concepts of yīn and yáng are then defined as its movement 陽 yáng and its retraction 陰 yīn. Perhaps we could think of the Great Extreme as the protogonos or Second Logos, and the Being-without-limits (wú jí) as the concealed Lord, the First Logos of the secret doctrine. Alternatively we could think of wú jí ér tài jí, the Being-with-and-without-limits, as parabrahman, represented as the “immaculate white disk within a dull black ground” in the archaic manuscript in SD I, 1.

6. Alchemy and the Human Soul

Stevan Harrell, in the opening sentences of his article The Concept of Soul in Chinese Folk Religion, states that7:

The concept of “soul” (ling-hun) [灵魂, líng hún] is central to the study of Chinese folk religion for at least three reasons. First, the idea of ling-hun underlies most notions of supernatural beings. […] Second, the loss of one’s “soul” is an extremely common explanation for many kinds of diseases and abberation, both mental and physical, that are treated by Chinese “sacred medicine.” […] Third, trance—a state common to folk practitioners in many parts of southern China—is invariably explained in terms of “soul” travel of spirit possession.

Elliott, whom we came across in the introduction, briefly describes the role of the shén (shen) and guǐ (kuei) in human psychology (op. cit. p. 28-29):

The Chinese concept of shen is closely associated with the idea of the human soul. The soul of a living man is conceived as having two components, the hun [魂] or positive component, which has three parts representing the three spiritual energies, and the p’o [魄] or negative component, which has seven parts representing the seven emotions. Shen and kuei are the ultimate spiritual influences, positive and negative respectively, which underlie the two components of the soul.

Legge in Chinese Classics Vol. I , p. 262, in his commentary to chapter 16 of The Doctrine of the Mean (中庸, zhōng yōng), formulates the same idea as follows:

神 [shén] signifies “spirits”, “a spirit”, “spirit”; and 鬼 [guǐ] “a ghost”, or “demon”. The former is used for the animus, or intelligent soul [魂, hún], and the latter for the anima, or animal, grosser, soul [魄, pò], so separated.

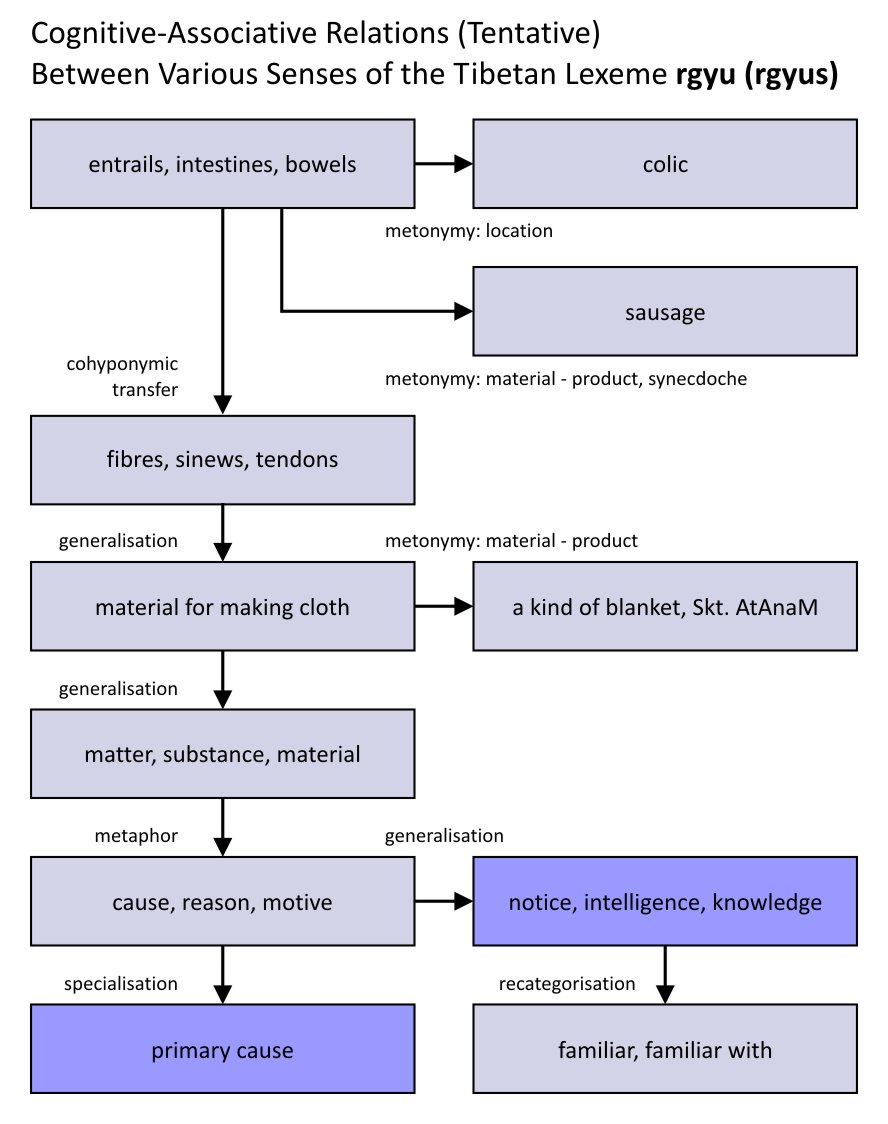

In an earlier stage of this investigation into the term fohat, I had already come across an original Chinese text where the term pò (魄) is used within the broader context of traditional Chinese religion, in The Secret of the Golden Flower (太乙金華宗旨, Tài yǐ jīnhuá zōngzhǐ), a Taoist alchemical work translated by Richard Wilhelm into German, first published in 1929.

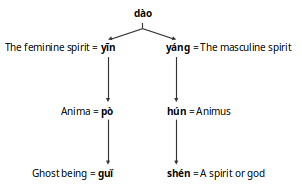

In 1931 an English translation was published, with an extensive commentary by Carl Gustav Jung. In Jung’s commentary (p. 65), a diagram may be found in which the various concepts are laid out on which the alchemical system is based. I reproduced it here in part. In this diagram we find the term pò (“anima”), and in the Chinese text the same character 魄 (pò) is used as in “fohat”.

In the diagram as it is partly reproduced here, we see Tao (dào) at the top, splitting into a masculine and a feminine spirit, yáng and yīn. The human principles hún and pò are labeled animus and anima. According to Jung’s commentary, the two human souls pò and hún, which are in conflict during the life of an individual. The terms animus and anima are the masculine and feminine meta-physical dimensions of the human being. They have a different sense than animus and anima in Jung’s writings on archetypes. At death they pass into guǐ (鬼), a ghost being, and shén (神), a spirit or god. It is clear that the same subject matter is discussed here as in HPB’s editorial note to the article Theosophy and the Avesta and in Medhursts dissertation.

If we compare the details of the model we find however, that the human principles HPB describes in her editorial note do not match those in The Secret of the Golden Flower. For example, if hún and pò are opposing principles, why do we find them related to ātman and kāma manas, which are by no means natural opposites? Perhaps we will have to conclude that the correspondence given by HPB, between the human principles and the Chinese terms is again a “blind”, and that we have to rely on our own understanding to find the actual correspondence here.

In the alchemical transformation which is described in The Secret of the Golden Flower, the opposing principles hún and pò are involved in the creation of the Golden Flower which is eventually dissolved into Tao (dào). In the commentary, Jung describes the hún and pò principles in man as logos and eros, the intellectual and passionate principles, which theosophists would perhaps call manas and kāma. He refers to chapter V of his own 1921 work Psychologische Typen, where he discusses the hún and pò souls:

Die Existenz der zwei auseinanderstrebenden, gegensätzlichen Tendenzen, die beide den Menschen in extreme Einstellungen hineinzureissen und ihn in die Welt — sei es in deren geistige, sei es in deren materielle Seite — zu verwickeln und dadurch mit sich selber zu veruneinigen vermögen, fordert die Existenz eines Gegengewichtes, welches eben die irrationale Grösse des Tao ist.

The existence of two mutually contending tendencies, both striving to drag man into extreme attitudes and entangle him in the world—whether upon the spiritual or material side—thereby setting him at variance with himself, demands the existence of a counter-weight, which is just this irrational fact, Tao. [1923 Eng. ed. p. 267, tr. H. Godwin Baynes]

So described, the process of unification is doubtlessly more than just unification of the intellectual and passionate principles in man. In the context of alchemical transformation of The Secret of the Golden Flower, the shén and guǐ apparently represent the spiritual and material in man, the heaven and earth aspects of the human entity, ultimately to be unified in Tao.

Epilogue

In studying the SD, and a fortiori its presentation of the text from the Book of Dzyan, one of the main questions is still “what were HPB’s actual sources”? Is the Book of Dzyan an existing text she translated from the secret books of Kiu Te, or their commentaries, from some mysterious language like Senzar, or did HPB derive her often innovative ideas from contemporary works by Medhurst, Legge and others? Was the information passed on through the Masters of Wisdom or was she perhaps only inspired by them, while getting basic information from publicly accessible literature? Without any doubt she was intensely driven by her ideas, throughout her whole life, and arguably these ideas together constitute an important framework, perhaps even more so for today’s world. That in itself may speak for her authenticity as a writer. We could argue that if there would have been no mention of books of Kiu Te, if there would have been no Masters involved, no foreign languages, that her ideas would still be have been of great value. For a serious reader however, she often made it very difficult to distinguish between different layers of message and packaging. The SD has multiple layers of interpretation, and perhaps we should not at all be surprised about that, as in esoteric literature that is often the case.

The themes of the different paragraphs of this article, “The Divine Breath”, “Father-Mother”, “Being is Non-Being”, “The Great Extreme” and “Alchemy and the Human Soul” may all be starting points for further study in the highly interesting field of Chinese traditional religion. Perhaps the esoteric world view presented in the SD can be of use as a study tool, a means to gain more insight into a world of spells, mediumship and shamanic travels. Only in the last few decades academic research in different disciplines seems to be moving in a direction where scholars are trying to understand these as cultural phenomena in their own right, rather than to depreciate them, trying to describe them as Western ideas in distorted form, as misguided religion or failed science. In the nineteenth century HPB already tried to understand religious phenomena from a universal standpoint, finding out the meaning of the elements of different religious traditions for humans in their personal lives and for humanity as a whole. It is this attitude which served as a model idea for the Theosophical Society, which only later resulted in its three objects. ■

Notes

1. Rev. Medhurst was a Calvinist (Congregationalist) missionary stationed in Malacca, Batavia, Shanghai and a few other locations in East-Asia from 1816 to 1856. His aim with this dissertation is to find a word with a meaning closest to that of the word “God” in Christianity. Moreover, Medhurst composed four dictionaries himself, including a Chinese-English dictionary, and together with other translators he was the first to translate the Bible into Chinese. The Chinese phrases in Medhurst’s text are without exception immediately followed by their English translation. In the present article, when introduced, Medhurst’s old style Chinese transliteration is each time accompanied by contemporary pīnyīn transliteration and Chinese characters in their traditional form. The word “Chinese” in connection to language refers to Mandarin Chinese.

2. Boer, Ingmar de, On the Etymology of the Term Fohat, published October 24, 2023 on the Book of Dzyan website, at http://prajnaquest.fr/blog/

3. Elliott, Alan J.A., Chinese Spirit-Medium Cults in Singapore, The Athlone Press, London & Atlantic Higlands NJ, reprinted 1990 (first published 1955), p. 27-29

4. The Dutch researcher J.J.M. de Groot wrote extensively on the different human souls, or aspects of the human soul, in shenism. In volume IV of his monumental The Religious System of China, published in 1901, he describes the different souls in human psychology, various religious ceremonies, and physical and mental pathology.

5. This definition in the Kāng Xī dictionary is a paraphrase of a quotation from a work by Mencius (孟子, Mèng Zǐ, 372-289 BCE). Within Medhurst’s quotations from dictionaries and other works, other (third) works are often quoted. Here we have four levels: myself quoting Medhurst quoting the Kāng Xī dictionary quoting Mencius.

6. In Chinese, the conjunction “heaven and earth” is also written as a nominal compound, “heaven-earth” (天地, qián kūn), in a similar way to “father-mother” in the Book of Dzyan (vol. I stanza II, śloka 10), or, if you will, like a dvandva compound in Sanskrit. Two modern translators of the I-Ching, Rudolf Ritsema & Stephen Karcher, in their 1994 translation (p. 115), render heaven and earth as “Heaven[and]Earth”, expressing the inherent unity and interdependence of the two elements.

7. Harrell, Stevan, The Concept of Soul in Chinese Folk Religion, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3 (May, 1979), p. 519-528

© 2023 Ingmar de Boer, published in The Netherlands

Download this article in PDF:

Download the Timestamp verification file of this article

Category: Book of Dzyan, Cosmogenesis, Divine Breath, Fohat, Great Breath, Motion | No comments yet