The term ālaya is a key term in The Secret Doctrine, which is connected to Yogācāra and Zen Buddhism. HPB uses it as the “basis of everything”, reflecting the Tibetan equivalent kun (all) gzhi (basis), apparently based on the paragraph “The contemplative Mahāyāna (Yogāchārya) system” in Emil Schlagintweit’s 1863 work Buddhism in Tibet. (p. 39-41) Schlagintweit refers to “the Gandavyūha, the Mahāsamaya, and certain others”. Those works will be interesting objects of study, to see exactly how the term ālaya is used there. In one of the most important Yogācāra scriptures, the Laṅkāvatārasūtra, ālaya is also used in the sense of the “basis of everything”, and it is certainly interesting to see how the term is used there, as we might do in the following article, first from a philological perspective, in part I, and secondly from a philosophical perspective, in part II.

The Laṅkāvatārasūtra was written (or consolidated) around 350-400 CE. Apart from a compiled Sanskrit version, we have three different Chinese translations and two different Tibetan translations. In 1932 the first English translation was made by Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki. He sees the terms ālaya and ālayavijñāna primarily as the “storehouse consciousness” where karmic remains, the vāsana’s, are stored as latent karmic seeds, until some time in the future, when they are reactivated to initiate actual karma. We can now go through all the different translations to see how the term ālaya is rendered in each case.

The Sanskrit Version

The Sanskrit word ālaya is composed of the preposition ā- (from) and the verbal element laya, which can be traced back to the root lī, to cling. A common meaning of ālaya is a “house” or “dwelling”. (Monier-Williams) Derived senses are “receptacle” and “asylum”. These may all be consistent with “storehouse”. As a noun, laya means a place of rest, residence, house, dwelling. It also means rest, repose, a pause, and lying down, cowering. According to Monier-Williams, the verb from the root lī basically means to adhere, to cling, to press closely, to lie, to recline, to settle. This root lī might be connected to another Sanskrit root, lip/limp/rip, to smear, which is related to the English “to leave” in the sense of “leave behind”. We can imagine that the sense of “house” has evolved from the basic sense “to cling”.

The Chinese Tripitaka

The earliest extant Chinese translation is that of Guṇabhadra, dating back to 443 CE, labelled Sung (Song) by Suzuki, after the ruling dynasty at that time. The other two translations are analogically labelled Wei and T’ang. Suzuki has prepared a Sanskrit-Chinese-Tibetan index of terms used in the Laṅkāvatārasūtra. From this index we can learn that the three Chinese versions all have 藏 (zàng) for ālaya, but only Wei and T’ang have in some places phonetic renderings.

The Chinese interpretation 藏 (zàng) simply means storehouse, depository. So, the common interpretation of ālaya, cf. Suzuki, as “storehouse”, is following the Chinese interpretation.

The Dūnhuáng Findings

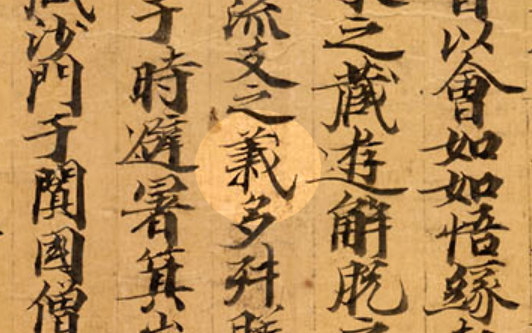

There are also a number of Chinese fragments of the Laṅkāvatāra among the Dūnhuáng findings, of the Song and T’ang editions. In some of these we can see that at least since the early 11th century, which was when the Mògāo cave complex at Dūnhuáng was sealed off, the T’ang manuscript was very faithfully copied. The first occurence of the character 藏 (zàng) in the T’ang manuscript is identifiable in some of the fragments, for example in Or.8210/S.6:

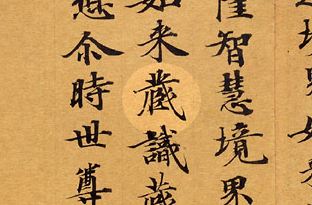

In the fragments of the Song edition, quite a few characters are different from the text in the Taishō edition of the Chinese Tripitaka. The Taisho text (T16n670) of the Song edition seems to be a modernised version, though at first glance textually it seems to be as faithfully copied as the T’ang version. Also in these fragments we can verify the use of the character 藏 (zàng), for example in Or.8210/S.5311:

According to the International Dunhuang Project database, this manuscript (Or.8210/S.5311) dates back to the 7th century. In connection with the Tibetan translation by chos grub, who based his Tibetan translation on the Song edition, it is interesting to know that the same rendering of ālaya was used in earlier Song manuscripts.

The Tibetan Versions

In his Studies in the Lankavatara Sutra (1930), Suzuki already mentioned that there are two different Tibetan translations. (pp. 12-15)

The Tibetan “version 1”, which is published in the Tibetan Tripitaka Peking edition (TTPE), Vol. 29 No. 775. It seems to be translated directly from Sanskrit. In the Asian Classics Input Project (ACIP) we find a text from the Lhasa Kanjur, still not completely entered, labelled KL0107, corresponding to Vol. 29 No. 775 from the Peking Tripitaka catalogue. In this Tibetan version the terms ālaya and ālayavijñāna are rendered kun gzhi and kun gzhi rnam par shes pa.

The Tibetan “version 2” was translated by “the monk chos grub” on the basis of the Chinese Song version, around the beginning of the 9th century. It can be found, for example, in the digital library of the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (TBRC). This version also renders ālaya and ālayavijñāna as kun gzhi and kun gzhi rnam par shes pa.

The Mahāvyutpatti Sanskrit-Tibetan glossary was probably composed between 800 and 838, which is around the same time the Chinese Song edition was translated into Tibetan by chos grub (version 2). Here, ālaya (entry 2017) is also connected to kun gzhi.

The primary sense of the word gzhi is ground, foundation, original cause, exciting cause, or even axiom. Another sense however is residence, abode. (Jäschke) Perhaps this combination has motivated the Tibetan translators to choose kun gzhi, the “basis of everything”, instead of a compound with, for example, the element khang, house, or mdzod, storehouse. Most probably they were familiar with the Sanskrit term as well, which, like the Chinese term, contains the element of house, abode, storehouse etc., which makes their choice for kun gzhi even more significant.

The Tibetan word gzhi, or gzhi ma, might be traced back to the reconstructed Proto-Sino-Tibetan root *ƛăj, meaning earth or ground, cf. the Starling Database, established by the late Sergei Starostin. Tibetan gzhi would then be related to the modern Chinese word 地 (dì), meaning earth.

At the time the Tibetan translation was made by chos grub, Buddhism in Tibet was still in the process of becoming what we now call Lamaism or Tibetan Buddhism. The developing religious culture may have already used the term gzhi, or kun gzhi, to indicate its “ground of being”, which became an important concept in the rDzogs Chen subschool of the rNying Ma lineage. For the Chinese translators the Tibetan situation was of course not a force to reckon with, so the interaction between Buddhism and the existing substratum might provide an explanation for the difference, between the semantic fields of Sanskrit ālaya and Chinese 藏 (zàng) on the one hand, and Tibetan kun gzhi on the other.

For completeness we should mention that Schlagintweit, in his Buddhism in Tibet (p. 39) presents yet another Tibetan word for ālaya, which is snying po, which generally means heart or essence. HPB, following Schlagintweit (p. 39), also presents “Nyingpo” and “Tsang” as Tibetan renderings of ālaya, in The Secret Doctrine (SD I, 48), where tsang evidently corresponds to our Chinese character 藏 (zàng).

Summary

The above data relating to the Laṅkāvatārasūtra are summarized in the following table.

| Edition | Language | Date | Translator | Form | Meaning |

| Nanjio | Sanskrit | ca. 350-400 | ālaya | ||

| SongTaishō 670 | Chinese | 443 | Guṇabhadra | 藏 (zàng) | 藏: storehouse; depository |

| WeiTaishō 671 | Chinese | 513 | Bodhiruci | 藏 (zàng), 阿黎耶, 黎耶 (both phonetic) | |

| T’angTaishō 672 | Chinese | 700-704 | Śikṣānanda | 藏 (zàng), 阿賴耶, (phonetic) | |

| TTPE Vol. 29 no. 775 | Tibetan | unkown date, from Sanskrit | unknown | kun gzhi | kun gzhi: basis of all |

| TTPE Vol. 29 no. 776 | Tibetan | 9th c., from Chinese Song ed. | zhu chen gyi lo tsa ba ‘gos chos grub (fǎ chéng) | kun gzhi | |

| English | 1932 | Suzuki | storage house, all conserving |

To pick up from what David said here about “tsang” in Schlagintweit’s book: I notice that he also used the spelling “tsang” for the Tibetan province (see p. 152, fn3 here: https://books.google.ca/books?id=xrsIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA152).

This would be the Tibetan term “gtsang” (གཙང་) or the Chinese term “zàng” (藏): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ü-Tsang. It is quite possible that this is the term Schlagintweit had in mind, but in his glossary it was given incorrectly.

As far as I can tell, in addition to being the province name, the Tibetan “gtsang” means something like “pure, clean, immaculate”. It’s equivalent in Chinese, “zàng” (藏), connects it to the Sanskrit “garbha”, which ties it back to the Tibetan “Nyingpo” (snying po). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddha-nature#Asian_translations

If this is the case, then the two terms Schlagintweit gives (Nyingpo & Tsang) would both relate to the “womb” or garbha, or to the tathāgatagarbha, which (please correct me if I’m wrong here) the Laṅkāvatārasūtra views as a somewhat equivalent term as ālaya-vijñāna.

“HPB, following Schlagintweit (p. 39), also presents ‘Nyingpo’ and ‘Tsang’ as Tibetan renderings of ālaya, in The Secret Doctrine (SD I, 48), where tsang evidently corresponds to our Chinese character 藏 (zàng).”

I had long wondered where Schlagintweit got the Tibetan terms “nyingpo” and “tsang” for ālaya, since the Tibetan texts uniformly use “kun gzhi” for ālaya. It makes sense that the “tsang” comes from the Chinese word. Schlagintweit gives the full spelling of this word in his Glossary of Tibetan Terms (p. 389) as rtsang, a word having no such meaning as ālaya. But this spelling is also a bit strange as a transliteration of the Chinese word. We would have to find Schlagintweit’s source to know for sure what was intended. In any case, both tsang and nyingpo are unfortunate errors for ālaya, which is uniformly kun gzhi in the Tibetan texts.